Conceived and developed by

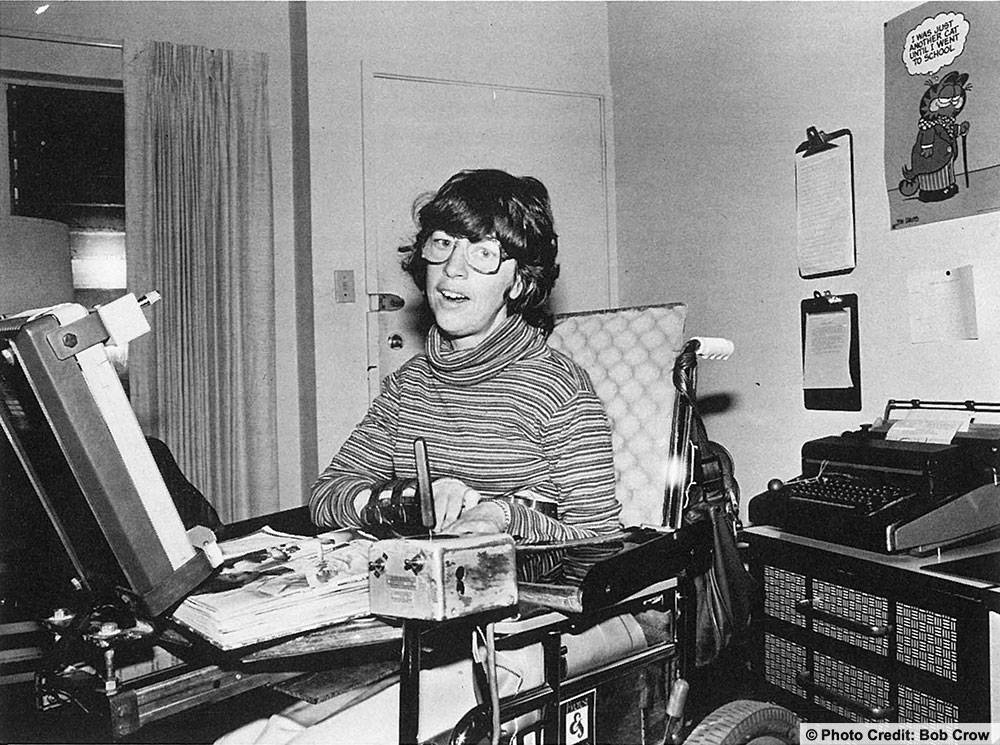

Ann Cupolo Freeman

Corbett Joan OToole

Victoria Lewis

Contents

Introduction

No More Stares

Until recently nobody talked much about being disabled. Especially disabled people. Most disabled people, including the women who put this book together, were the last ones who wanted to point out that we were different.

Until recently nobody talked much about being disabled. Especially disabled people. Most disabled people, including the women who put this book together, were the last ones who wanted to point out that we were different.

Well, times have changed. Now disabled people see that this silence has made it harder for us to figure out how to live our lives. We have found that if we don’t talk about problems, nothing changes. We’ve learned that we can’t live in a vacuum. We need to know what other people with disabilities have done so we can have some idea about what is possible for our future.

There are a few success stories that disabled persons are told as children. For boys, it’s FDR, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the first and only American president who had polio. For girls, it’s Helen Keller.

Helen Keller was a remarkable deaf-blind woman who found language and expression late in her childhood working with her partially-sighted teacher Ann Sullivan. Ms. Keller’s life contains a very dramatic story that starts with complete isolation and ends up with international recognition and admiration. It’s such a good story that it’s been told again and again-in books, plays, movies, tv programs—until now the story is larger than life. At least bigger than many of our lives.

It’s sometimes hard to see what Helen Keller’s triumph has to do with the smaller frustrations of being disabled: not being able to go to the movies because of a flight of stairs; not wanting to walk your dog because people stare at you; not having the money to pay for a modified van, a TTY (telephone adapter for deaf people), or an Opticon (reading device for blind people).

So the women who put this book together decided that more stories needed to be told. The women who talk about their lives in No More Stares represent all races, all disabilities, all age groups. Some of their stories are as dramatic as Helen Keller’s though the women themselves aren’t famous. Others talk about more down to earth things like how they learned to drive, or how they clean house.

You may feel you have something in common with Helen Keller, or you may not. But after reading all the stories in this book, you might begin to feel that you share common experiences with other disabled women.

The disabled women who put this book together definitely feel this way. Though we are of different races and disabilities, we share a lot. We’ve all been told, some more, some less, that we’re not OK, that we’re not equal. We’ve all been stared at, we have been kept out of schools, jobs, concerts, parties, careers, etc. We’ve been kept out by physical barriers (like stairs and the lack of aids for vision or hearing impaired persons) and mental or attitudinal barriers (excuses like, “You’ll upset the customers if we put you in the front office,” or “A deaf person can’t teach.”)

Those of us who worked on this book have a discovery we want to share with you: because we talked to each other about our everyday lives as disabled women we have felt better about ourselves, more able to live life as fully as we can.

How you feel about yourself is what’s most important. When you feel good about yourself you can grow and change. But everybody, disabled or not, has trouble feeling good about themselves. Everybody at times feels either too fat or too thin, too short or too tall&mdashtoo awkward, too dumb. Most girls walk around hating themselves for not looking like a model.

When you can’t go to the same movies or parties as everyone else because there’s no ramp; when you can’t attend after-school activities because there’s no sign language interpreter; when you can’t read the same books as your friends because they’re not in braille; or when no one will take the extra time to understand your speech, it can really get hard to feel good about yourself. It’s hard but not impossible, because none of those things are your fault. We wrote this book to prove it.

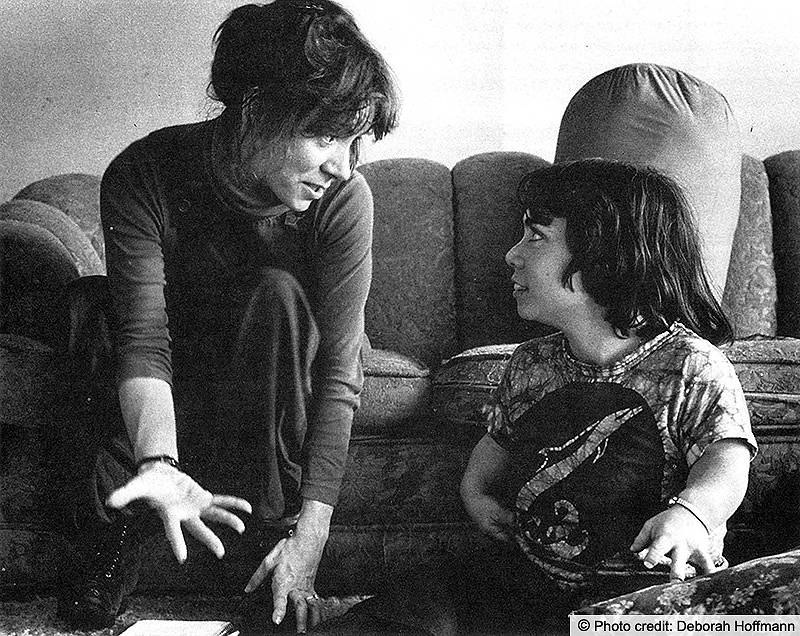

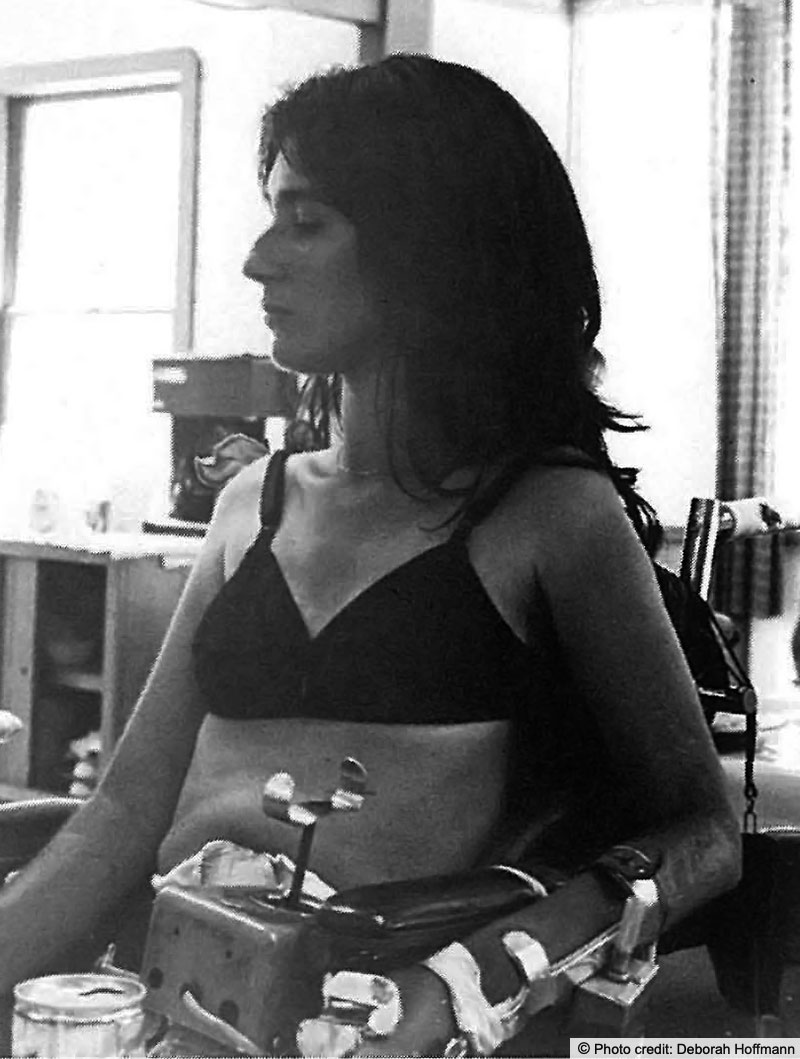

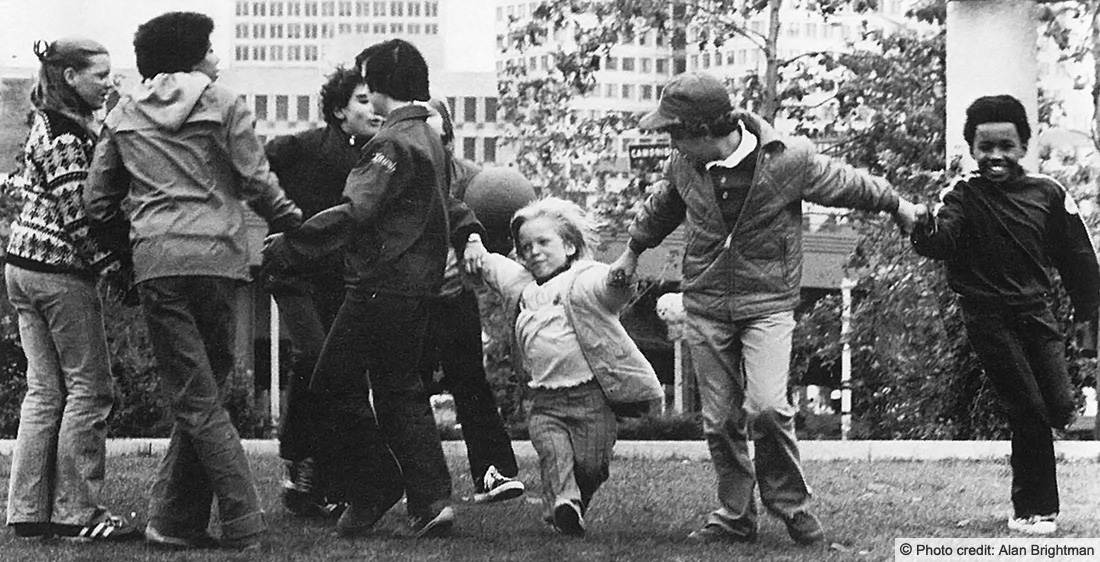

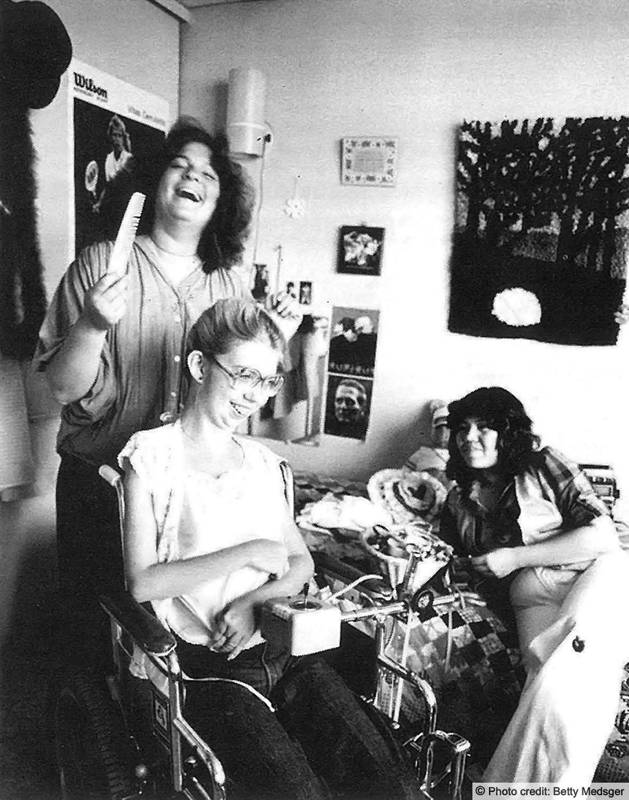

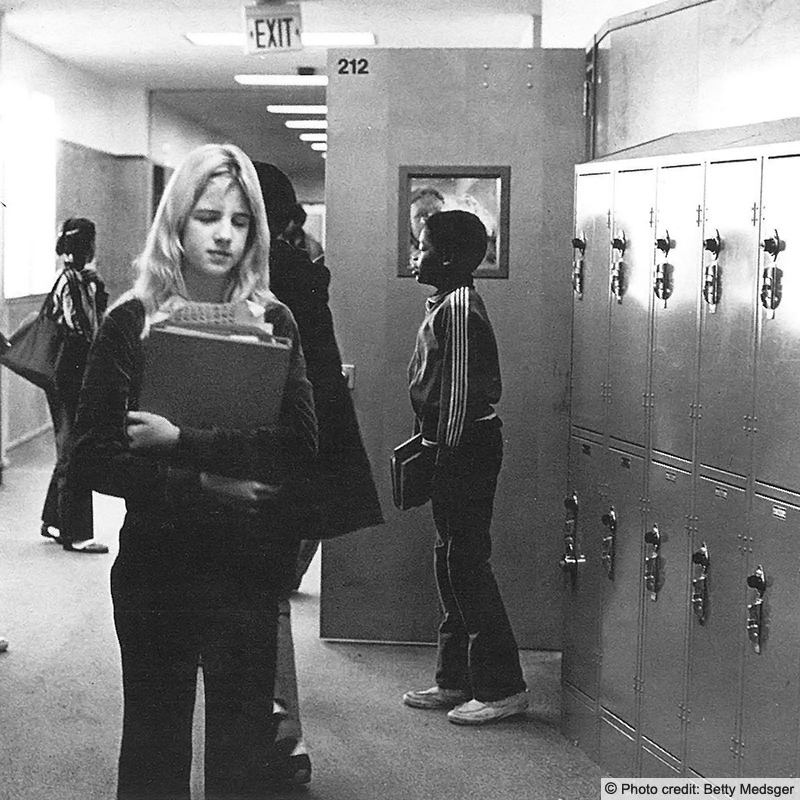

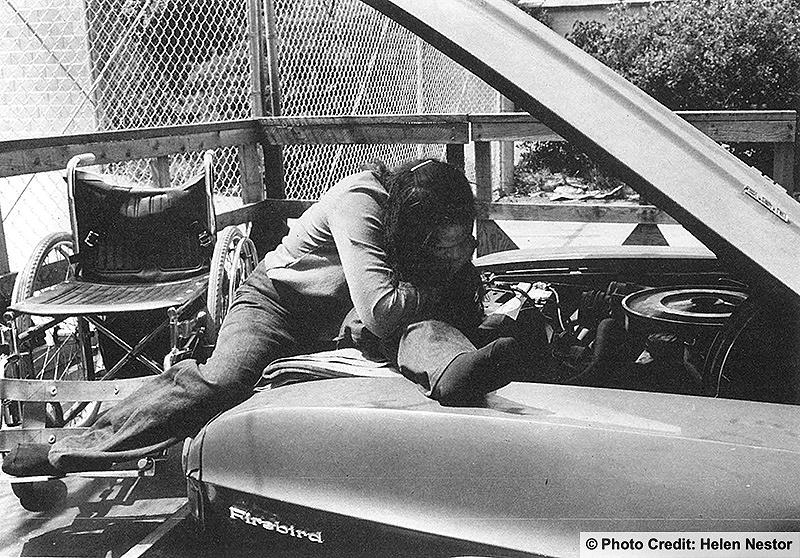

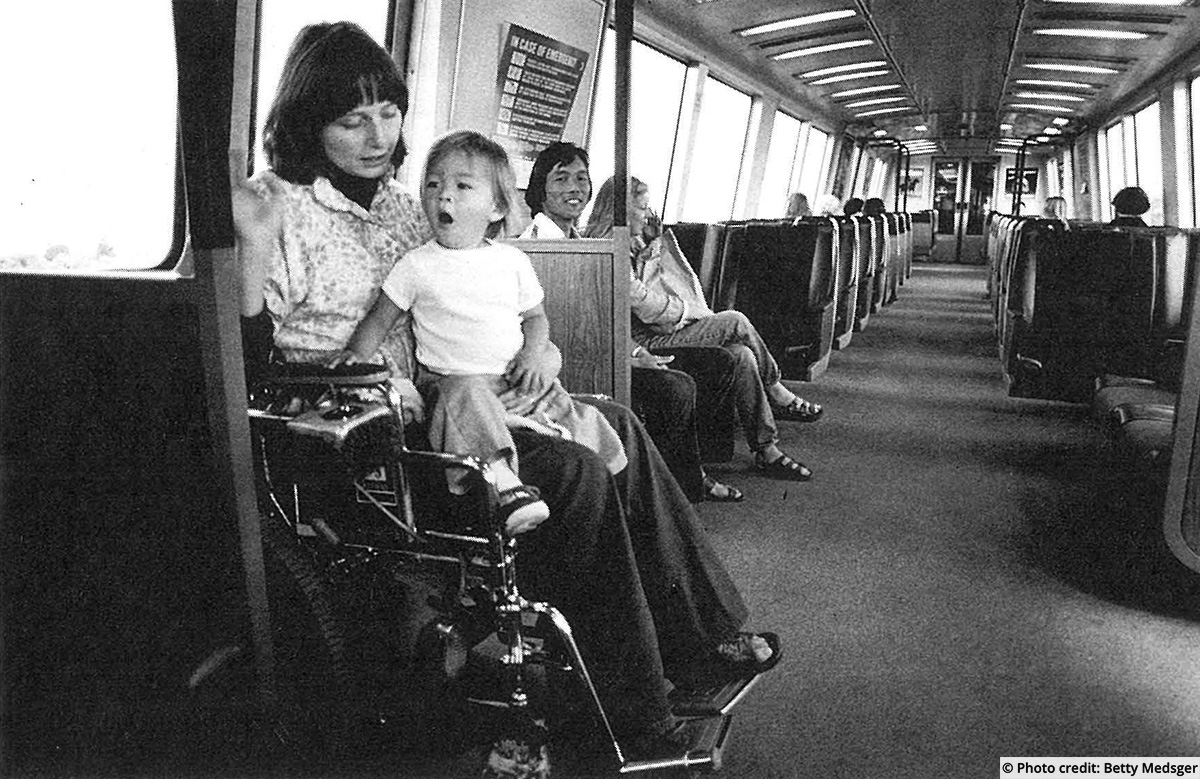

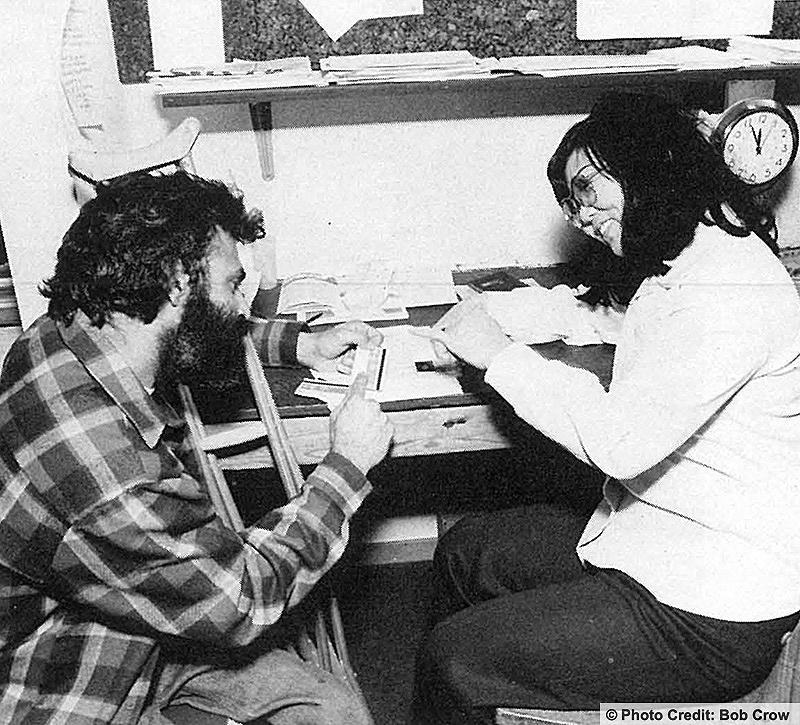

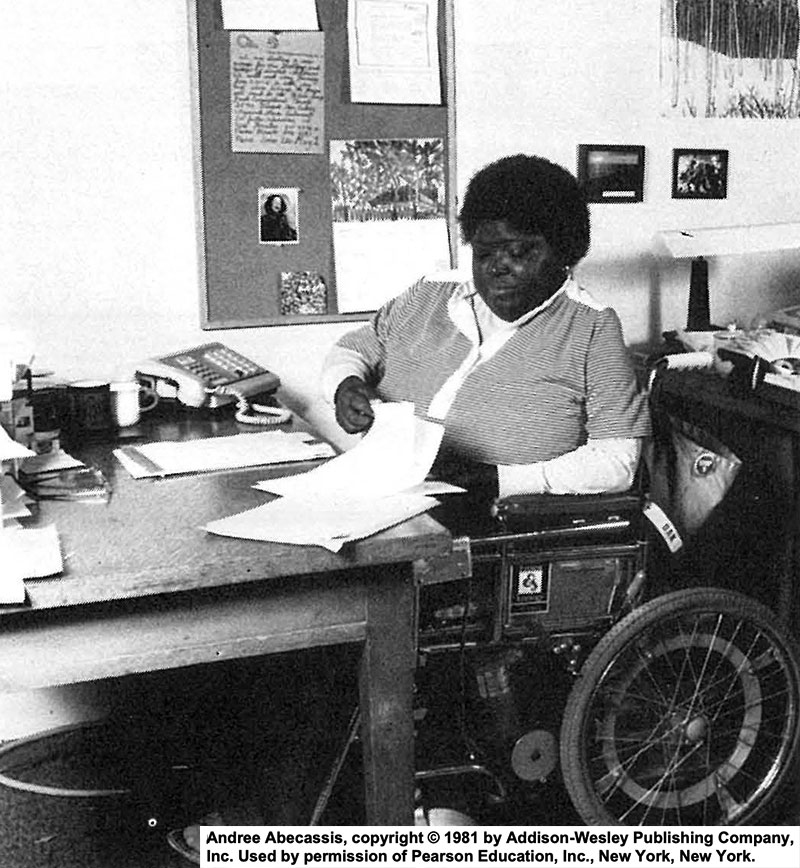

We hope that by reading this book, that by hearing of the thoughts and feelings of a wide range of women with disabilities, by looking at photographs showing disabled women doing just about every conceivable thing, you might feel better about yourself and more excited about the possibilities of the future.

We hope many people, including men and non-disabled people, will enjoy this book, find it interesting, even illuminating. But to begin and end with, it’s a book for and about disabled women and girls. No More Stares tells the story of Anna, a young girl who in her own funny dramatic way is at war with the world that makes her feel different. When we first meet Anna she has been attending a mainstreamed school for the first time in her life. Though she’s made friends and does ok with the books, things aren’t going well for her. In fact, if Anna’s waging a war, it seems like she’s about to surrender. Or is she?

Staring

I was riding the subway one day and this woman came up to me, sat down by me and said, “Oh, my God, it’s such a shame! Such a pretty girl, such ugly hands!” (My hands and feet were deformed at birth; the condition is called syndactylism.) So I said to her, “So would it be better if I were all ugly?” She giggled and mumbled something about a tragedy. I said, “I don’t think it’s such a tragedy. You ihink my hands are ugly, you should see my feet!” and got off at my stop.

– Bree, syndactylism

Until high school I went to special school for the physically handicapped…. We had monthly clinic visits by an orthopedist who would come, like a circuit judge, to the schools…. I would have to get out there in my underwear in front of the doctor, the physical therapist, a couple of teachers, maybe the principal, other kids and parents. I’d be paraded around and had to listen to my “case” being discussed.

– Victoria, cerebral palsy

When I was younger, I was extremely aware that someone was staring at me, even though I couldn’t see. If I made a mistake and ran into a tree, someone would see me. Someone would know that I wasn’t normal.

– Sheila, blind

I have Down’s syndrome. I can’t stand it when people yell at me and come up to me and say things. That hurts my feelings. Some people don’t treat you right. I don’t like people calling me mentally retarded. I want them to call me by my real name. When people call me names, sometimes I yell back, sometimes I ignore them.

– Ann Marie, Down’s syndrome

Going through the first year after the accident happened to me, I was stuck with scars on my body. I knew that kids were looking at me because of my burns but their facial expressions were really scary. They’d look at me like I had some kind of disease or something. They would draw pictures, as if I looked like a monster, and they would put the pictures up on a tree. I felt so hurt inside, and once in a while outside. I wish I had told them, “Well, I happened to be burned, but I still have a brain.” I didn’t think of what to say. I would just take it in and accept it.

– Lois, deaf

People stare at you if you’re different. They can make you feel like a Martian. I never really wanted to go out because I was so selfconscious. My family would say, “You have to go out, we’ll take you to the beach.” I wouldn’t. So my father would get off work at night and we’d go to the movies. The only show I’d go to was the late show that started at 10:00 o’clock. It was dark in the streets and in the theater. My father would wheel me out as soon as the lights came up.

– Terry, post polio

If I had one wish, it would be that people realized how their staring hurts me, and that I can’t help being small. I was just made that way. I guess other people just don’t know how it makes me feel … or else why would they stare?

– Ginny, short stature

You want to know what makes me really uncomfortable? Every once in a while there are these people who come up to me and don’t say anything. They keep real quiet and just look at me. It’s as if they’re going to find the answers or something all over my face.

– Laurie, blind

Being Alone

Many of the things I like to do on my own are the little things, like picking out my clothes for school. Most people don’t even think about these things when they’re doing them, but I have to…. Another thing I like to do on my own is to go out without someone looking over my shoulder all the time. Sometimes I just like to take my cane and walk a little.

– Laurie, blind

When I’m alone I like to read books. I like to look at the view outside my window and meditate by myself.

– Susan, deaf

For a long time as a young woman I was in a leg cast living in my parents’ house on top of a hill. I couldn’t get off the hill for months at a time. Luckily I had art. Every day I went into this little cubby hole and painted at this fevered pitch. Maybe if I hadn’t had arthritis I could have accomplished the same thing by climbing a mountain.

– Ginny, rheumatoid arthritis

I don’t like being all alone because it gives me a feeling of loss. I think it all started when I went to the hospital and separated from my family. There was almost no communication. I think I have been alone for so long and for so many years that I really hate the idea.

– Lois, deaf

Being alone is still a new experience for me. For years I didn’t like being alone. Being alone meant trying to find a different way home from school so that I wouldn’t run into kids who would know I wasn’t popular. Being alone meant nobody likes me. Now I’m more comfortable—like being alone in my car, driving and thinking. It’s a hard road to learn to be comfortable with yourself.

– Judi, cerebral palsy

Sometimes I feel really alone because of my disability. I am hard of hearing and although I can function fairly well in both the hearing and the deaf worlds, I do not, at times, feel a part of either world. I am not totally accepted as deaf because I can talk and lip-read fairly well, and I am not totally accepted as hearing because there are times when I cannot hear and use an interpreter.

– Missy, hard of hearing

The time I spend alone is Sunday—my housecleaning day. I really enjoy that day: I enjoy cleaning. Just me and my dog. People know they’re not welcome at that time. No one comes. No one calls.

– Margie, blind

I love playing the piano when no one else is around. I sing and get really dramatic.

– Ann, short stature

Self Image

Early in my disability I had a rejecting attitude towards other disabled and have only just got rid of this. I didn’t want to mix with disabled people, didn’t want to be associated with them. I wanted to pass for non-disabled . . . I wanted desperately to be accepted as “normal.”

– Elsa, paralyzed

I always had a fear that I was going to be rejected because I couldn’t look a person in the eyes (I focus off to the side). How would a person feel if I told them I loved them and I was looking past them?

– Barbara, visual impairment

The first time I played on the varsity basketball team, I tried to hide my burns by wearing tight pantyhose to cover up my legs. But the coach wouldn’t let me play until I took them off. He sent me to the restroom. I cried in there, not wanting to show my burns and be stared at. I was called on to hurry out and get on the court with my team and in seconds the game began. That was the beginning ofmy self-confidence.

– Lois, deaf

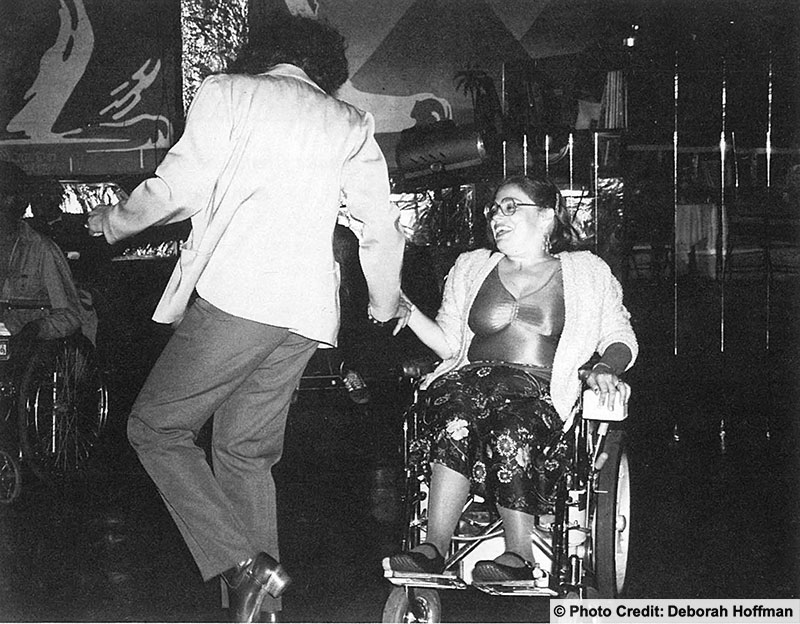

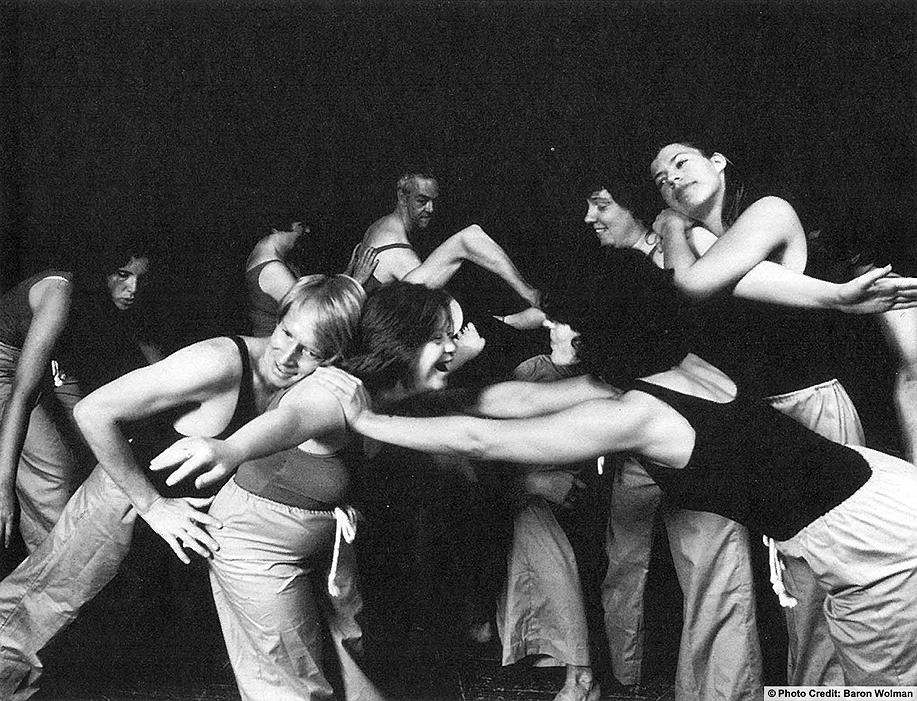

Wheelchair sports have been very important to me. I get an almost orgasmic feeling from excelling, winning … being able to control my body and do sports well … I would be the last person to go out on the beach in a bikini, but I see myself as being attractive.

– Roseanne, post polio quad

Being profoundly deaf hasn’t broken my heart. I just changed my way of living. You can always find a way to substitute for what is lost.

– Joanne, deaf

Once I learned that American Sign Language is my language, I developed a strong sense ofidentity as a deafperson and a more positive self-image.

– Barbara, deaf

My first period was truly welcome…. At last my body had done something right … something every female body is supposed to do.

– Anonymous, scoliosis

After my injury I didn’t care what I looked like. I met visitors in my robe with a cap pulled over my head. One day I said, “I don’t care what I look like.” Immediately I thought, “How ugly that sounds.” I started taking care of myself and I realized that my appearance affected how people treated me. It made me feel good that people appreciated how I looked. I started taking the time with clothes and make-up that was natural to me before the accident. It worked.

– Re’gena, spinal cord injury

I have diabetes, I think one o f the things that is the hardest about it for me is that I don’t look sick so the type of invalidation I get “Wow, I never would have guessed it. You look so healthy!” I don’t need to hear that. I’d like to talk about some of the things that get me down.

– H.S. Senior, diabetes

Just last year, after getting together with various kinds of disabled women from all over the country, I compared my disabilities with theirs. I listened to their problems, what they’ve gone through and what they were and are confronted with. I realized that I was no worse off than most of them. From these days I cried and awoke to see who I really was. I talked with my close friends, asking them to be honest and tell me what they thought about me as a person. I got very little negative response, so I grew to like and love myself even more. Today I know who I am, if I am loved, wanted and cared for. But most of all I love myself for what I am now.

– Lois, deaf

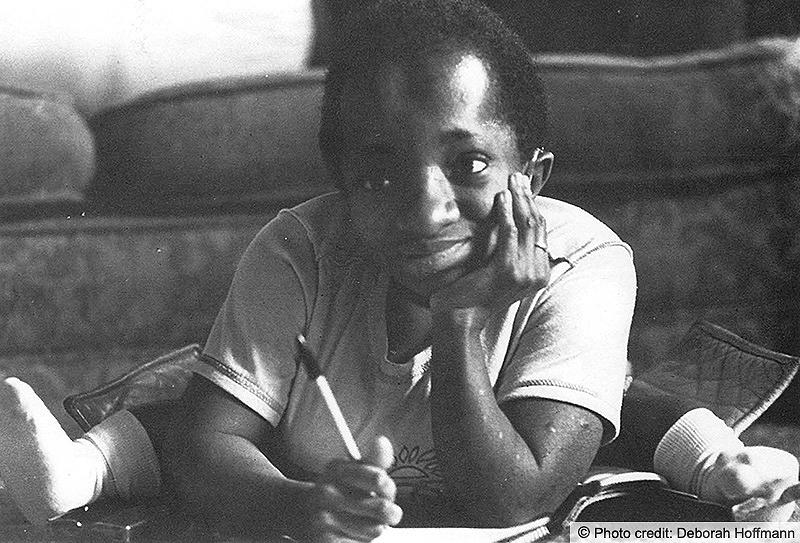

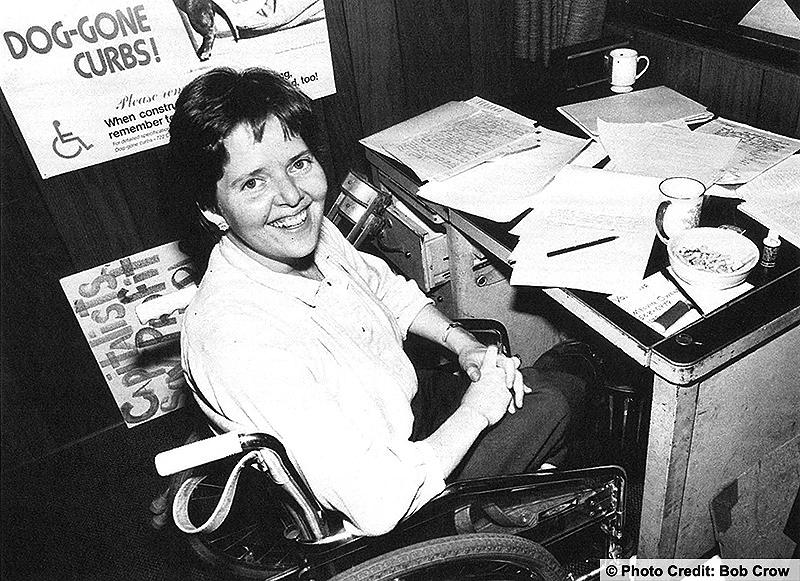

Being black, I’ve found that I can’t always get what I need…. I became disabled and pregnant in the same year. My whole life was turned around. I had already left home and now I was back living with my mother. I was told to settle for just staying at home but I couldn’t accept that and I didn’t.

– Jackie, chronic lung infection

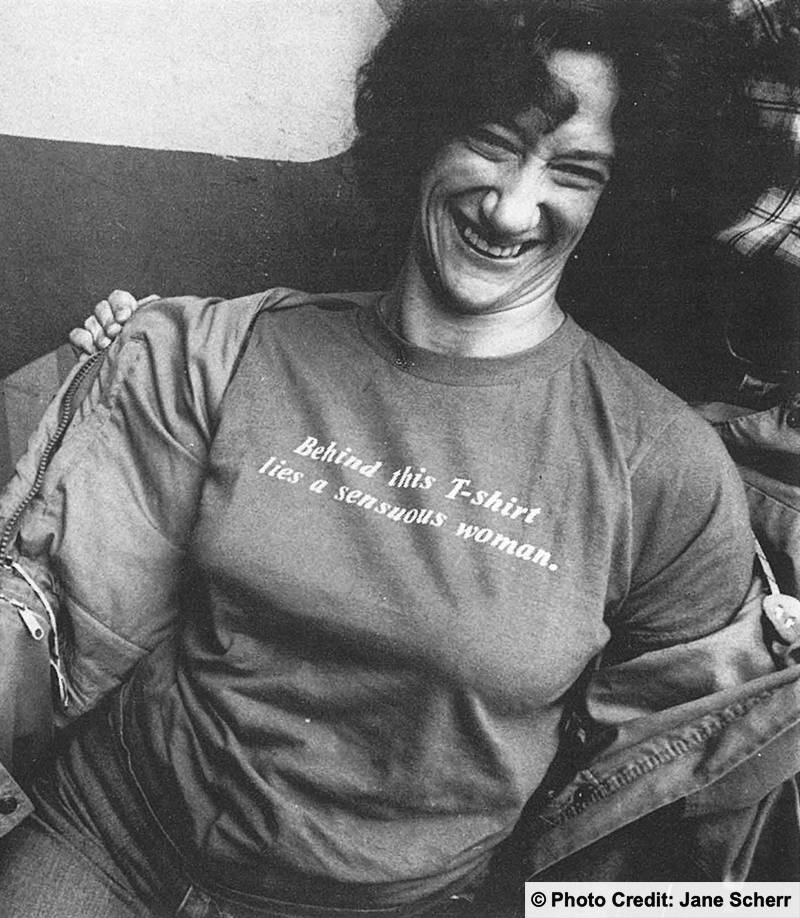

Who am I to give advice? I don’t have any secret … Unless it’s to be yourself. When you look in the mirror, you are you, and there’s nothing you can do about it. And I’d rather be happy about it and laugh, than cry and have tears.

– Jill, amputee

I have really had to work to keep up with my sighted peers. I have had successes as well as failures. I think that people with disabilities often strive so hard to compete with non-disabled peers that they forget that it’s ok to gauge small successes. Both disabled as well as non-disabled people have the right to have successes as well as failures.

– Lori, partially sighted

Some deaf children look down on sign language. They do not want to sign in public because people will say that they are “DEAFAND DUMB.” They get that attitude from their parents or teachers.

– Mary Beth, hearing impaired

In the past couple of years I have become aware ofmy body and have decided it’s not distasteful. Before I had concentrated on developing and using my mind. My body I’d just cover up so I looked ok. Now I’ve decided my body is fine: it’s just different from other people’s. Now I adore my body, dress up. I swim and take karate which centers just on me and my body.

– Margaret, post-polio

Once when I was staying in the hospital, my sister and I got in wheelchairs and started racing through the halls. I really liked it. I had never moved that fast before. Then in junior high school I started playing wheelchair sports. Sports have helped me to gain confidence in myself. Confidence was something I had lost a long time before.

– Debbie, cerebral palsy

I had this image of myself as a big blob, no shape just dead meat.

– Barbara, arthrogryposis

I was born without legs and with a right arm that ends where most people have an elbow. It’s an unusual body, but it is a body. It houses a living person and lets me do many of the things I want to do to fulfill my life.

– Sara, amputee

School

When people ask me if I’m in special ed. I get embarrassed. I’m afraid they’re going to make fun of me or laugh. Sometimes I just say “Yeah.” They ask me why and I say because I’m slow. I used to get laughed at.

– Cheri, learning disabled

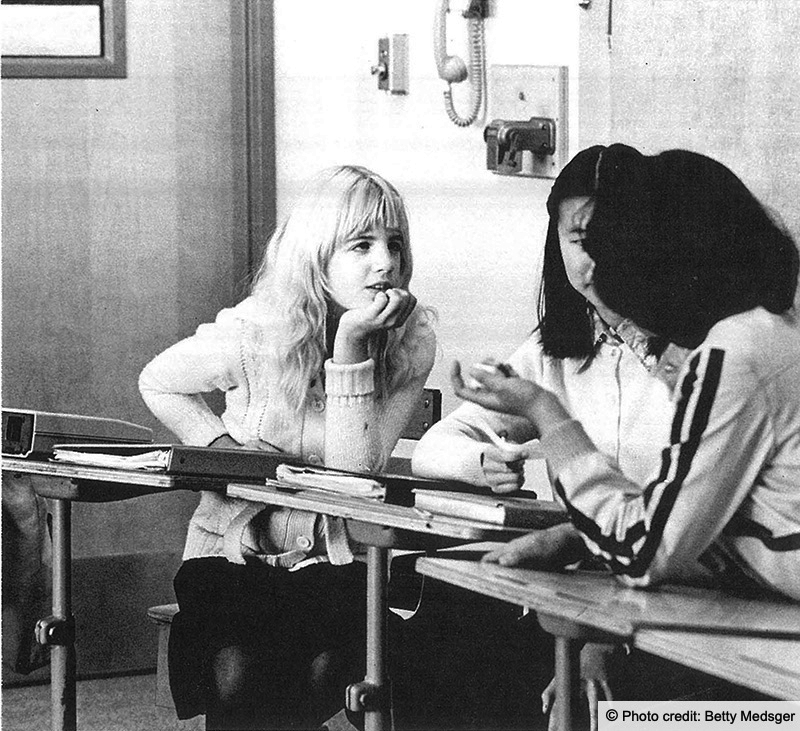

At first it was real scary being with regular kids because I’d been at a school where all the kids had problems like mine. But after everybody got used to me and I got used to them, I started to love regular school. Having friends who understand makes all the difference in the world. It makes you feel free.

– Antoinette, blind

I don’t like it in this school. I would prefer to be with deafpeople. I don’t try out for sports and I would in a deaf school. The hearing students repress the deaf students. I’m tired of being in a hearing school.

– Rebecca, deaf

I remember interacting in school with other kids who were disabled, kids who had clubfoot or were severely bowlegged. We were all the butt of everyone’s ridicule and exclusion. There was a camaraderie among us because we were mutually hurt. … That’s had an influence on my life.

– Ann, blind

At a special school, they treat you differently. Like ifyou don’t do something, it’s ok, you don’t have to try. In regular school they encourage

you. They say, “You should try it. You never know.”

– Martha, post-polio

In the regular school I was stuck with able-bodied kids who had never seen a kid in braces before. I wasn’t treated as a girl. This was very painful to me, because I hung around with a group of boys who were really my good friends. They treated me like one of the fellows, and I did not feel like one.

– Victoria, cerebral palsy

In the school for the blind, I didn’t like it that I was only with a lot of blind kids. But I needed that school: I needed the braille skills, the mobility training. The school had its good points and bad points. It was hard to be back at 10 o’clock on Friday and Saturday nights as a teenager. You couldn’t spend the night even if you had your parents’ permission.

But, I had really started to fall behind in my math in the regular school even though I have an aptitude for it. Math is very visual and without special aids you can’t get it. In the school for the blind I was able to make up two years in one.

Then I went to a high school that has been mainstreaming kids with disabilities for twenty-five years. Nearly every teacher in that school has had a blind kid in their class at least once over the years. And since the school is set in a community where disabled people are very visible, the non-disabled kids in the school are more aware and accepting than in other schools probably.

The only really bad school was four years ofgrade school I spent in a country school in a multi-handicapped class. I had a couple of hours of math and spelling a week. The rest of the time was spent watching TV and playing scrabble and ping pong. That’s the truth.

– Margie, blind

When I arrived at the school for the deaf when I was 10 years old, all I knew how to do was to spell my name and count. That was it. My previous teachers in regular schools had passed me because they didn’t know what to do with me. In the deaf school I learned to sign and finally began to understand what was going on in the world.

– Lois, deaf

I envy the mainstreaming of the educational system today. When I first attended school, the only other disabled person I knew of throughout all of my pre-college years, was a girl with leukemia in high school. Even then, I was not aware of it until she had passed away and I read about her in the dedication o f our yearbook. Nowadays, there are more and more disabilities mainstreaming into the schools and it is not as isolating as it used to be.

– Missy, hard of hearing

Friends & Relationships

Gazers vs. Starers

I had friends who just wouldn’t let me become bitter or wrapped up in self pity or any of those things that destroy people.

– Linda, spinal cord injury

I used to feel that the other kids might not want to play with me because I was different, smaller and stuff like that. But now I don’t feel that way at all; I just feel that I’m included, and that I have a lot offriends to be with.

– Ginny, short stature

After I moved away from my parents I began to meet people and get involved at the university. I felt less and less lonely. I found that if you get out and do the things that you like to do, you will meet people with whom you have things in common … that’s how friendships are formed.

– Lori, partially sighted

I’ve met an awful lot ofreally nice people. I enjoy the conversations I have with people as they push me along. I like people and always have. If I were MISS INDEPENDENT, I would never meet any people-communication is what life is all about to me. I get my ups and downs from other people.

– Kathleen, paraplegic

Throughout my teenage period, I got along fairly well with the same sex rather than with the opposite sex. Though at different times I had two steady boyfriends, I never was serious with them. I was cautious, wondering what drew them to me and if they were ever going to accept me for who I was. I could hardly trust and relate completely to them. Because ofmy burns, I decided to forget the idea of having a boyfriend.

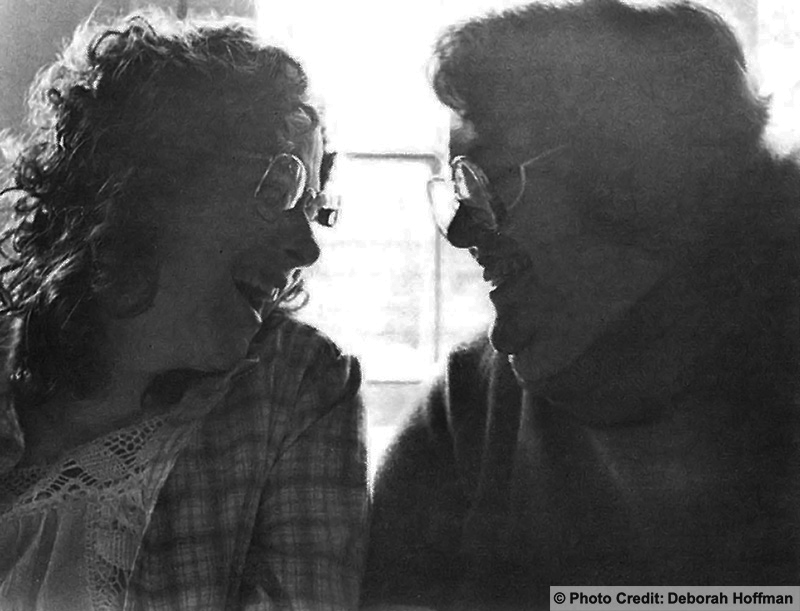

But in my second year in college I met a fellow who was so gentle and understanding. We dated several times before I realized I was in love with someone who cared for me just as I was. He finally convinced me I was wanted and loved, regardless of my burns. I was able to express my feelings openly for the first time to someone I came to trust. Because I was “old-fashioned,” I never discussed future marriage plans with him for fear I would be too aggressive; I didn’t want to lose the close relationship we had developed with each other. I waited patiently for about two years, when he finally asked me to marry him. Was it real or was it a dream? I didn’t want to believe him so I overlooked his request for a week, then he brought it up once again. This time he made it clear we were going to be married for true. We were married two months later.

– Lois, deaf

I love to dance. My grandmother would always laugh at me, tease me, “You don’t mean boys dance with you?” One time we went to a wedding and a boy asked me to dance, a slow dance. He took me back to my grandmother and when he didn’t ask me for another dance, she said, “Of course he didn’t come back. He probably felt your leg braces.”

– Rosalba, post polio

I am a student, so I keep fairly busy. I have many friends but I have not found anyone who I would like to become involved with. I think that my disability has played a small part in this. It will just possibly take a little more time to find a suitable companion.

– Lori, partially sighted

Because of my physical condition, I was given limits by people. They assumed that they knew all about me because they read about cerebral palsy in their college textbooks.

– Laureen, cerebral palsy

I have been blessed in my life with exsome- onetraordinary friends . . . . They encouraged me to apply to the university even if it meant going and banging on the door and demanding acceptance. I had been brought up to think that I had nothing to offer the world but to accept the role that society decreed, with pity thrown in for good measure.

– Pat, post polio

My husband is great, but his family hates me because I’m disabled. His friends always told him, “You’re so good-looking, why do you go with someone like her?”

My husband is great, but his family hates me because I’m disabled. His friends always told him, “You’re so good-looking, why do you go with someone like her?”– Rosalba, post polio

– Sheila, blind

– Gaile, visual impairment

– Lynn, mentally retarded

I make friends because I want friends.

– Ann Marie, Down’s syndrome

It Isn't Always Easy

Most Indian reservations didn’t have hospitals till 1973. I was trampled by horses when I was thirteen. I could receive no medical care in the local hospital without the signatures of six white families. By the time the papers came through, the hips had begun to set. I was severely disabled for eight years. Then I finally received decent medical care which included artificial hips. Today I can walk.

– Terry, dislocated hips

There are no sidewalks in the area I live in and the streets are so bad that when I do go for a walk, it feels like every nut, bolt and screw will vibrate out of my chair and all the teeth will fall out of my head. My chair does not fold because of the bellows under the seat so I cannot fit into a sedan or taxi.

– Shirley, post polio

All the time I was growing up and after wards there were a lot o f buildings I could not get into or had to have people with me to carry me into them. I really feel, particularly in public buildings, that we have the right to go into any room we want. When I know I can’t go to the bathroom, I get pretty nervous.

– Mary Elyn, post polio

As I was growing up, I experienced frustrations and isolations … sign language was forbidden … so there was always a communication barrier during my growing-up years.

– Alice, deaf

When I was taking the SAT, the College Entrance Examination, they didn’t have a large-print version. It took me eight hours to get through that test!

– Barbara, visual impairment

When it comes to how to get someplace fast, that’s a big problem for the deaf. People who don’t have tty’s have to drive all the way to where they want to go and see who they have to see even if it’s a hospital or whatever. Also, if they have to deal with the cops, they get a ticket. They always have to ask someone to make some calls for them.

– Lois, deaf

I found a man in California who says I can learn to drive, but the adapted controls cost $2500!

– Valerie, post polio

When people in power realize that it is cheaper to pay an attendant to take care of someone than to run a nursing home for disabled people, the better it will be for all disabled people.

– Linda, spinal cord injury

Moving Up & Out

When I got my first power wheelchair … I felt like a queen I We went to the grocery store that night … everybody said I was beaming. I hadn’t learned to drive it well, and I was going up and down the aisles. I almost hit some of the displays. But I was happy. I was just exuberant. To be able to do something under my own power was wonderful.

– Tarri, Friedreich’s Ataxia

Independent living? It means to have your own room. Keep your room clean. Like, sometimes when my boyfriend’s real sick I take him to the hospital or he takes me to the hospital. We go to different places. Like, we go to the Oakland Zoo, or sometimes to the San Francisco Zoo, or we go to the airport.

– Lynn, mentally retarded

My father was most patient during my first experience of driving. He placed his two VW’s on the street so I could learn to park, and pass my driver’s test. When I went for the road test, two police officers went with me. They were interested in the special foot controls … and I gave them a detailed explanation of how I worked them.

– Norma, double arm amputee

I am twenty years old and have only recently moved out on my own. When I first left home, I had no idea what to expect. I found myself in strange surroundings. I was not sure if I could do everything that I needed to do for myself. As time went on and I began to become familiar with my surroundings and abilities, I found myselffeeling much better about my situation.

– Lori, partially sighted.

The first time I picked up Amy’s harness, I felt I could see again, I really felt free. It was a beautiful feeling. Amy and I are like a ballet team … When we have time, we walk three to six miles a day.

– Judy, blind

My parents were convinced that I wasn’t capable ofliving on my own. I decided that I was, even though I didn’t know anyone who had done it. I even had a rehab. counselor come out to the house to explain to them that I could live on my own but they didn’t believe him because he was blind, like me.

Then I started getting scared. People started saying you don’t have any sheets, any towels. I also didn’t have any money.

One afternoon my mother and I were sitting in the dentist’s office and we started having the same argument about my moving out that had been going on for a few years. I wanted to, she didn’t want me to. My mother had to leave the room for a while. All of a sudden, someone sitting in the room said, “Hey, if you want to move out, move out.” And I said, “You’re right.” And after that there was no turning back. One of my brothers said he would help as soon as I had turned eighteen and graduated. I did move out but I wasn’t successful at it, had to keep going back home, until I spent some time at an independent living center for blind people.

– Sheila, blind

I was ready when I ieft the school for the blind to live on my own. On my seventeenth birthday, I decided I’d move out in a year. During that whole year, I bought towels and dishes and stuff with money saved from my SSI check. I had everything I needed when my eighteenth birthday came.

– Margie, blind

One day during the spring break from college, I had the nerve to ask my father for a car of my own, thinking he would say okay. But instead, he shook the world out of me with a message, as if my dependence on him for financial support must have drawn to an end. The words came out like, “If you want a car, earn your own money and buy yourself one.” From then on I made up my mind to do what I knew would be best for me and for my future well-being.

I could have persuaded him to buy the car for me anyway, and I could have paid part of the expense. But I didn’t want it that way. I wanted to work for the summer, and I tried to ask my mother to help me find a job when I came home from college for the summer. She was really reluctant, and I felt really frustrated. I decided to write to the mayor of my home town. He passed the letter on to some group, and that group wrote back to me and said they would have an opening for a summer job.

Later when I came home, my mother told me that someone from that office had come to the house to ask about me. My mother was really stunned: she didn’t know if I was really doing the right thing, because it looked like maybe I was going over someone’s head. But I had to have a job. I knew that being deaf and black, there might not be anything for me, but I felt I needed to begin to be independent and responsible. I wondered if I got the job. I wanted my mother to call for me but she was reluctant. I really became frustrated. Luckily, I got a letter saying that I was hired. The interesting thing was that I was the only black person there and the only disabled person there.

I feel that the best way anyone can get anything is to fight for themselves, no matter what their sex or race or religion or color or culture. That was really my first step to lead me into fighting back against my disability.

– Lois, deaf

Every human being, except the hermit in the desert who raises his own food, is dependent on other people – for material things like food and roads, all the way up to intangibles like love and a sense of purpose in life. In parts of Africa, water is so scarce that the women of some tribes spend eight hours every day hiking to and from the area’s well to gather enough water for their families’ needs for one day. For people like us with running water, such a way of life seems almost inhuman, an insult to human potential. Probably all the women visit together during that long walk, but still . . . Well, it’s the same for me. Without help, it takes me three hours to get dressed and out of bed in the morning. With the help of a paid attendant, I can be in my van and on my way to work in 45 minutes. I am independent to the same extent that a non-disabled person is; I can choose where I will work, who my friends are.

– Paula, post polio

Work

Ever since I was ten, I thought I might be a teacher of the deaf. My teachers would send me to other classes to help teach their students. I felt I had a natural teaching power within me. One day I was interviewed by a teacher and she asked what I wanted to do when I grew up. I said, I want to be a teacher like you. She said I couldn’t be a teacher, no deaf person could be a teacher. My world fell on me. Not until college at Gallaudet did I learn I could teach.

I was the first deaf teacher in San Francisco . I spent fourteen years teaching in many different schools from the pre-school level to junior high.

– Joanne, deaf

I sing to let the world know I’m alive. I love street work. I love to sing, I love to hear the cup shake, I love to hear people talking as they’re going by. I love it when they stop and talk to me. I like their perfume and the brush of their fur coats. I like to feel the flap of other kinds of coats as they go by.

– Baybie, street singer, blind

I think I am a good teacher. Even with my handicap, I felt I was better than some teachers with all their faculties. I never doubted my ability.

– Chris, spinal cord injury

One day we had this great lesson. Everybody was sitting on the floor reading a story. One o f the kids raised his hand to ask a question, and when I called on him he asked, “How do you go to the bathroom? “I really wanted to laugh, and I did a little, because I thought the lesson was involving the whole class and here this boy wasn’t thinking about the lesson at all. I answered the question for him, and then we went on. I think it’s important for the students to know that if they have a question about my disability it’s okay for them to ask it, and they will receive an answer.

– Judy, post polio

There’s no difference in being a celebrity and disabled except when they roll out the red carpet for me, they tape it down so I won’t trip.

But it’s just a matter of time before they realize that I’m just like other comics and we’re all just like each other. Comics have a drive to make people laugh; I have that drive. It’s not the cerebral palsy that’s the basis for my comedy; that’s just a gimmick.

– Geri, comic, cerebral palsy

Of course, I can’t be in an all-singing and all-dancing musical, but acting is as much spiritual as physical and the wheelchair doesn’t bother me a bit. The fact I can’t use all my body doesn’t make my acting any better or any worse. It’s just different.

– Lisa, actress, spinal cord injury

Parenting

I’ve been a single foster parent off and on for nine years and more recently an adoptive parent. I had been going through procedures to adopt a child for the past four years.

Because I’m disabled, I’ve been called upon to prove myself more to be a capable parent since the adoption agencies don’t know what we can or can’t do. Many disabled people don’t believe that adoption agencies will allow us to adopt. It can be frustrating and take many years but you must persevere. After all these years, I’m at the point where I’ll be getting a second child. Many disabled people feel guilty about adopting a child because they think that they’ll not be able to offer a child as much as a non-disabled parent. Well, that’s just not true.

– Charlotte, double amputee

As far back as I can remember, I’ve wanted a family. I can remember the astonished looks on the faces ofpeople when I stated emphatically that I wanted six children as I sat in my wheelchair.

– Leslie, post-polio

Everyone discouraged me from having children, but once they knew this was what I wanted, they helped. I did fine with the pregnancy. I had to go off cortisone, but with the hormonal change that is normal with pregnancy, I felt fine. I had a few problems but no different from anyone else.

– Ginny, rheumatoid arthritis

The doctors back east said we can’t help you. They thought I ought to have an abortion. Abortion never crossed my mind.

I had nausea and vomiting all the way through. My blood pressure fluctuated; I went into premature labor; I almost had a miscarriage. … But she just wanted to be here: she wanted to happen. The main thing is, we love that baby and she loves us.

There’s no way I can change her diaper … but I feed her. She goes in the shower with me. We stay out for hours. We go every-where—to the Flea Market, the Co-op. I like to show her off, the proud mom. Lots of times she just sleeps. She loves it … the more she moves, the happier she is.

– Sandy, spinal cord injury

To bathe them, I had a small portable baby’s bathtub which I slipped into a large cloth bag (like a pillowcase) that I made to fit the tub. This made a sling inside the tub for the baby to lie in. Then I had two hands free to bathe them and to keep my balance also.

– Marie, paraplegia

It was my son who made me return to life after my injury: knowing that I had a son to raise. He would ask me different things like, “Well, what are you going to do? Aren’t you going to walk?” I’d say, “No, I don’t think so.” Then he’d say, “Well, I’m going to make you get up and put your braces on.”

– Riua, spinal cord injury

I can’t see anyplace where the disability was harmful to my family. Sure, I had to be inventive about holding, lifting and handling my children. But I never made a big deal about being disabled, it was apparent. As my sons became older, they began to help carry things for me, help out. I think it was good for them, helped them to mature. It gave them something other people didn’t have.

– Ginny, rheumatoid arthritis

In Their Own Words

Nancy Becker Kennedy

A fter my injury, a diving accident that left me a quadriplegic, I was delirious for three weeks. That was the only way my psyche could deal with the shock. I was absolutely terrified that I’d become a social leper, that my social life was over. Luckily I was crazy enough to want everything I wanted before the accident: I wanted an exciting career, I wanted to be in love. And eventually those things happened. At the beginning I thought being quadriplegic was the most horrible thing on earth. I still can’t imagine there being a more horrible thing that someone can experience and still be alive.

But also it’s a kind of marvelous thing to go through: An odyssey to hell and back. If everyone could do it and come out ablebodied I’d really recommend it. I think it does a beautiful thing for you. It was profound and wonderful even if a lot of it’s hideous. Once you’ve become disabled you can’t be on automatic pilot anymore. You can be a human pinball, batted around and kept going by others. You’ve been spun out, either out of control or under your own control, the choice becomes clear.

I’ve discovered that things I thought I couldn’t live without, a job, I can live without. And that’s wonderful feeling. I want a life without fear. So I like these cherry bombs that shake up my life. I love comfort and security but I learn from the upsets.

Susan Vaccaro

Last spring my deaf friend said, “Why don’t you try out for cheerleader?” I said , “What? You’re crazy! I can’t do it! I’m deaf!” She said, “Try it.” Then some hearing friends said to try it. I thought about it and finally decided, OK. So I practiced. I was really frustrated because I couldn’t hear the words of the cheers and I couldn’t see anyone’s lips because we would be in a line. My interpreter helped a lot and said, “Don’t give up.”

The day of the tryouts I was so scared I didn’t go to school My interpreter called on the TTY. As I went to answer the call I thought, “Oh dear, I’m stuck now.” I told her I was sick. She said, “Too bad, I’m coming to get you.” I had to go. I was stuck.

So I tried out. Everyone was yelling for me. An hour after the tryout I found out I got it. I was really shocked. My interpreter was crying. I realized I was really a cheerleader.

It’s not easy. I have to memorize everything alone. I can’t use words for movement cues so I have to look to the right and left of the girls in line and use my peripheral vision. If I’ve forgotten my hearing aid (I don’t hear words, just sounds with it), then I have to keep everything in my head: the timing, the speed. But everyone says I’m good.

Nansie Sharpless

Deafness is a much more severe barrier to a professional career than is being a woman. Everything I do is “wonderful, considering.” It is hard to develop mature and responsible habits when nothing is expected of you.

Deaf people are often treated like children, incapable of responsibility for their own affairs. Women are supposed to be passive, not too competent or independent. I don’t fit…. It has taken time for people to get used to me. As a professional woman who is deaf, I represent a study in contrasts.

I have never made any secret of my deafness. On the other hand, I have always stressed the fact that I do have job skills to

offer my prospective employer in exchange for any inconvenience my deafness may cause. If asked point blank, I explain my limitations matter-of-factly and mention how I cope with them. Otherwise, I do not dwell on the subject of deafness.

My first career, that of medical technology, is one that is traditionally a woman’s job. And my second career, that of biochemistry, is the “feminine” area of chemistry . . . being a woman has influenced my career choices.

From my experience, I think scientific research is a practical, rewarding profession for a deaf woman, and I would hope to see more deaf people enter it in time.

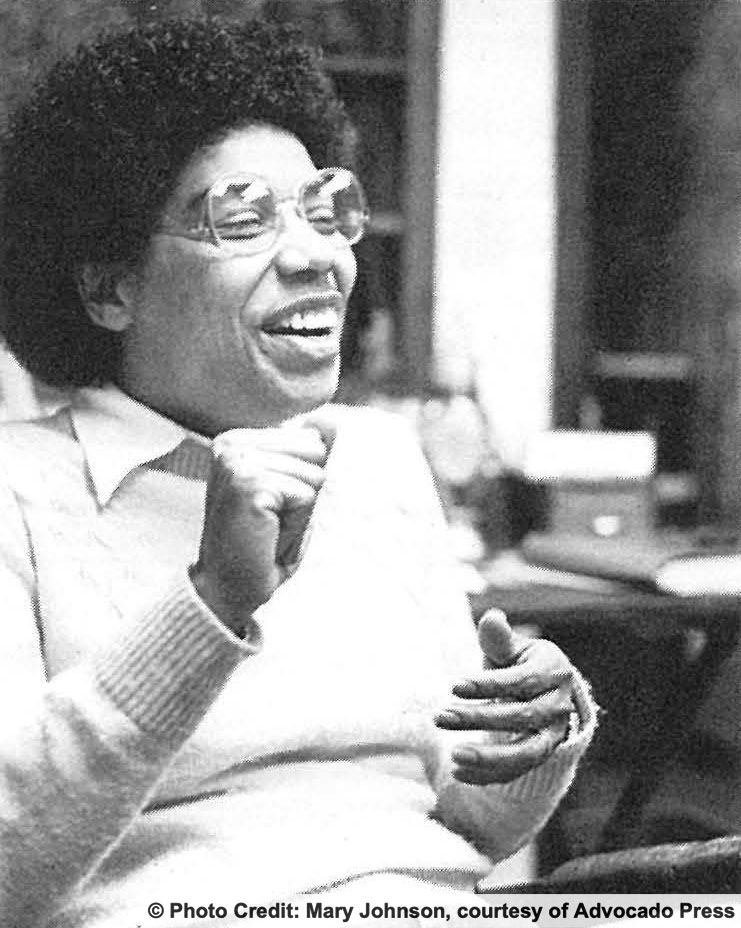

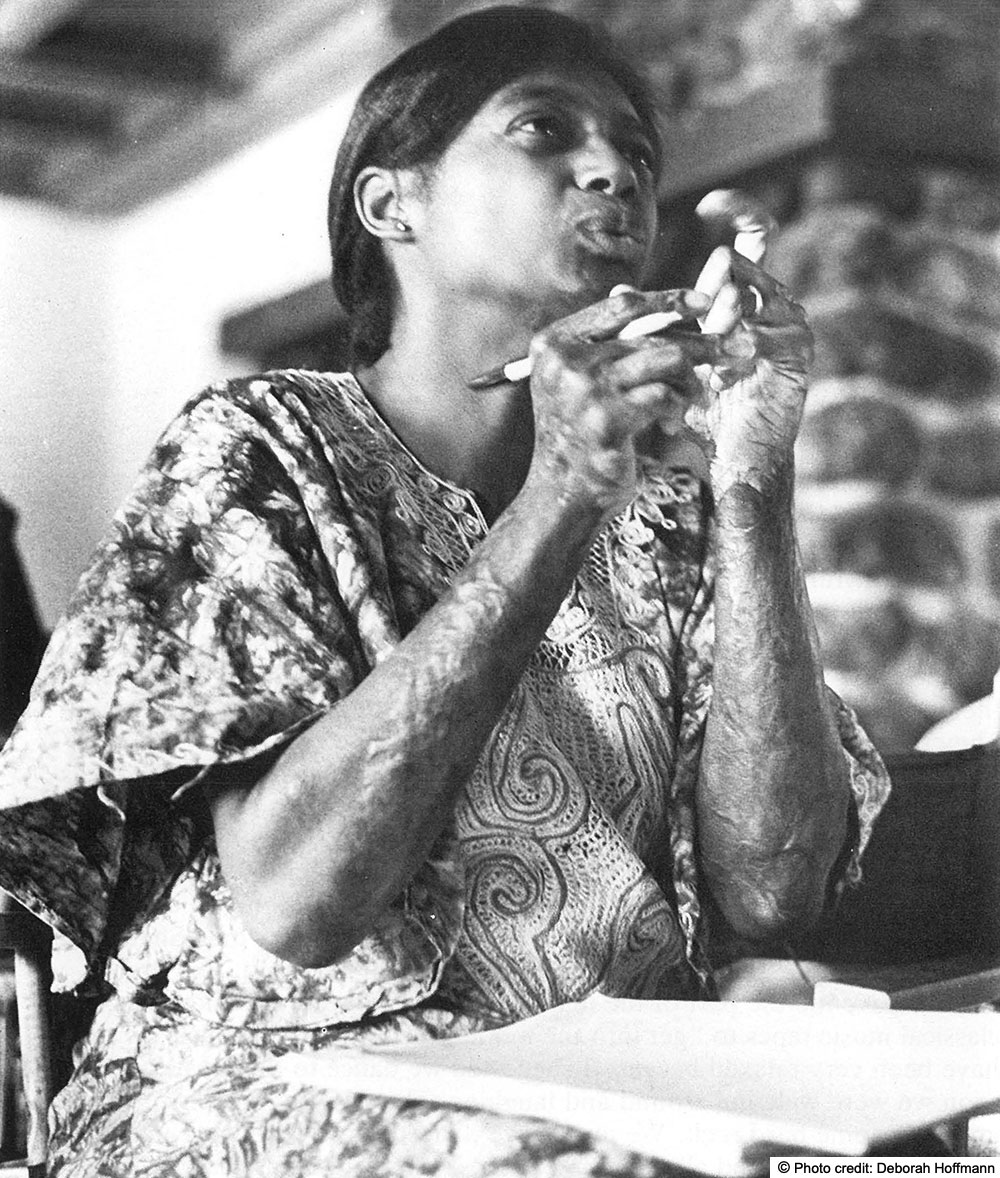

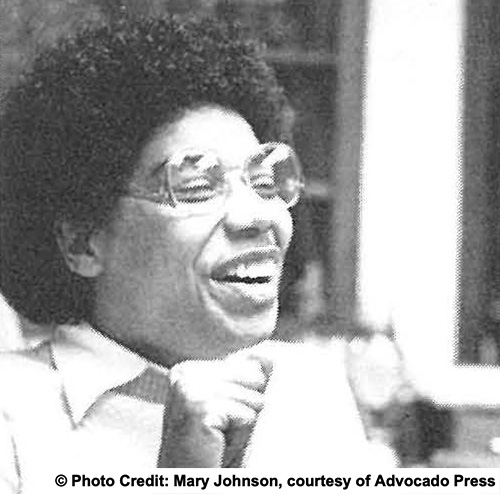

Lois Dadzie

Lois was born in the deep south. She is the L youngest of six children, three brothers and two sisters, and grew up on a farm. She is the only disabled child in her family. Lois was not born disabled . She became disabled at the age of five after she was burned in an accident. While in the hospital the doctor gave her medication which caused her deafness. Here she discusses her school experiences:

All the three teachers that I had in public school passed me, not because I was really learning but because they “felt sorry for me.” They felt that was the only thing they could do. That attitude was really common with black communities, especially in the South.

It was hard for me at first at the deaf school. Most of the students didn’t look at me as a deaf person, they looked at me as a burn victim, and their facial expressions made me feel even worse than with the hearing students. My favorite teacher was my math teacher. He was the one who encouraged me to keep up with what I was doing. He was the one who brought the idea of college to my mind; he was the one who would tell me that someday I would be this or that. I’d say, “Huh, it’s not possible;’ and he’d say, “Yes, you can.” Sometimes he’d tell me about how hard it had been for him to go to school. He told me, “You will be the first black girl from this deaf school to go to college and come back and teach the other kids.” “Well,” I thought, “that’s not a bad idea.”

During my junior year, my class from the black deaf school was bused to the white deaf school. I felt one of the teachers there was really prejudiced because she was using the signs as though they meant “nigger” instead of “black.” She thought that we blacks were ignorant. I was really furious! When I was in my senior year at the white deaf school, the teacher asked if we knew who was valedictorian. I didn’t want to say anything because I knew that she would start cursing, so someone else in the class said,”It was Lois.” It was me. The teacher said, “Why, you are not supposed to be, because you have not been at this school long enough.” I said nothing. My classroom teacher selected from everyone’s name and grades put in together; I had the top grades.

The next week the principal came to the typing class and informed me that I had passed the Gallaudet entrance exam, the college exam. I was not shocked. I kind of expected it. I found out that I was the only one in the whole class that passed. I really felt honored to be the first black from that school to enter college.

On graduation day, my family, in-laws and relatives and friends, all came as a group to my graduation. Graduation was at the white school. I had to give a short presentation. I really felt good that day because my uncle from New York flew in, and so did my uncle from Florida. That was a really big change for me. I knew then that my people really cared about me and cared about my future.

In the summer right after I graduated from high school, I was making plans to go to college. I took the train all the way to Washington, D.C. My cousin met me there. She took me to Gallaudet and that was something really different from my high school. It was a lot of competition for me there. I really felt different compared with how I lived at the old school. There was no supervisor always watching me. I could get around anywhere on campus. I could even go off campus by myself. Before, I couldn’t even go out without a supervisor going with me or someone, some adult, accompanying me. I also made a lot more friends. I joined activities. Most of my friendswereblack.Therewereveryfewofus and we were really close to each other because we felt like we were lost and disconnected from our own people. Every weekend we would get together and have a party. We would go out; we really had a ball.

The teachers there were ok. They were not as understanding or as friendly as teachers had been in the black deaf school. Their attitude was, “I see you during the day, but at 5 o’clock I’m gone for the day.” I also came to realize that at Gallaudet the students controlled things. At the deaf school, things were managed by the supervisors and the teachers. Also, I began to see black and white students together.

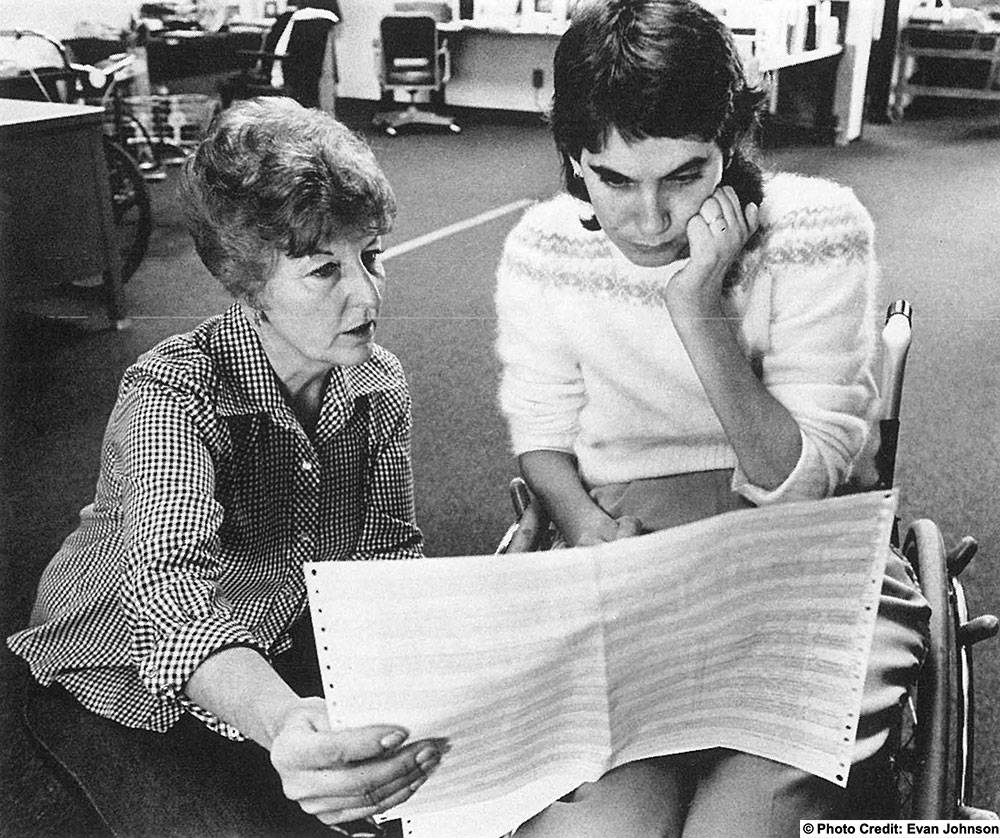

A fter college I had mixed feelings about whether I was going to be as successful in a career as I had been in school. I was surprised to get a job a couple of months later with an organization serving the handicapped as an evaluator/trainer. With this job experience, I had some kind of self-confidence, support and understanding as to what I wanted to do in my career.

Unfortunately, I had to go on maternity leave after six months of work. When my first child was four months old, I returned to work on a part-time basis as an instructor with the low-functioning deaf. A year later I was offered a full-time position as a Rehabilitation Specialist, gaining rich experience, from which I was later temporarily promoted as acting coordinator of the entire hearing impaired program with the departure of the then coordinator.

My high hopes of becoming the coordinator were shattered when the administration discriminatorily hired someone else whom I thought was incompetent to work with the hearing impaired, especially the low functioning deaf.

Somehow, I felt that I had been unfairly denied the opportunity to fulfill my dreams and goals because of my disability, race, and sex. It was really humiliating.

For the next two years, I ended up staying at home as a full-time mother and housewife, trying to see if that was what I really wanted to do. Instead of being the same happy person I used to be, I was getting depressed. I began to withdraw from society and didn’t want to be bothered by anyone, except those few close friends who were encouraging me. Depression and dislike of myself were killing me; I knew it was time to get out of the house and back on the go. The problems were to find some people who would understand my feelings and what I had to go through. I even tried to look for work but I didn’t really feel that I was ready to get back into the work world. One day my husband brought home some job announcements for me to look through, one from the west coast. It sounded good and since I needed a break, I thought, “Why not try it and see?” I checked into it and was given the opportunity to try. This was the time that I came across people who understood my problems and what I was facing. The doors once again opened for me to take the opportunity to build my confidence in myself, which I’d lost over the past few years. I started working part-time, doing the kind of work I really enjoyed so much in the beginning. As the job came close to ending, I wondered what I was to do next.

Of course, I didn’t want to go back to being a full-time housewife and mother and feeling depressed. When I asked two people from the office what I should do when the job ended, they quickly said that I was wanted to work in the main office out west. I thought about moving, leaving my family and friends. It was a very difficult decision to make.

After many weeks, I finally made up my mind to move on out west, not just because of the job but also because I needed a new life. The move has changed me a lot. I think I’ve adjusted pretty well to this new environment. So far I’ve met many new friends, and I love my work.

Norma L. Henley

From the time I was 14 until I was 34, I lived in Valley Home, a nursing care facility for people with cerebral palsy. For the first ten years I was a good girl. I completed junior and senior high school. But I began to feel very unsatisfied. The home took care of my physical but not my emotional or intellectual needs. They couldn’t see me as an individual.

I linked up with a regional rehabilitation program to help with my goal at that time of going to school and someday making my own living. I thought I could do that and still stay in the institution. And so began my gradual awakening to the idea of independent living with the first step being a disabled student program at a university.

I could have stayed at Valley Home for the rest of my life, could have been taken care of forever. But what would I say on Judgment Day when God asked me what had I done with my abilities? Eventually I made the administration angry enough that they decided I didn’t belong there. By the time I moved out I was a rebel. I wrote my parents:

Dear Dad and Mom,

Something extremely exciting is happening in my life and I want to share it with you.

I have an appointment to see the coordinator of the Disabled Students Program at the University of California to check out their residence program. I have already filled out an application. If I am accepted as a student, I am moving in September.

I haven’t made this decision without considering all the aspects. I know this is quite a shock to you both but I truly believe you, my dearest parents, want what’s best for me. Right now this is the best opportunity I have had to further my education in a much better environment. I also want to learn how to live independently with attendants which I so desperately need at this stage of my life.

I need a life I can control 99% of the time and won’t have to tolerate a number of people who are supposed to be responsible for my and others’ well-being and don’t do their best. It’s plain dehumanizing for me to live in the Home much longer. Whenever I am away from here, I feel so alive, but often here I feel like going six feet under.

The next place I live I want to feel like I belong and I’m an equal. When something wrong happens in my life, I want to know it’s my mistake and not the stupidity of others.

Here’s how the residence program for the physically disabled student works. For the first ten months you live in a dorm with 24- hour support services, learning all aspects of independent living while taking academic courses at the University. Then when sum- mer comes, you are ready to move out into an apartment in the community with attendant care.

This is what I really want, and again, need. You are aware that for years I have been very discontent with living here at Valley Home, and they are all aware of it too. I’ve outgrown institutional life.

Most people I’ve talked to about the opportunities at the University have urged me to go for it, so that’s what I’m doing. They’re helping me get an electric wheelchair and a communicator to talk to people who don’t know me and aren’t used to my speech.

I realize this is difficult to accept, but I’m praying I will have your blessing because it would make it much easier for me. You know I have potential that I’m not reaching. You have instilled in me the courage to continue my life in a more independent way.

Love, Norma

And then, my parents wrote back to me:

Dear Norma,

We received your nice, long letter … just know lots of your thoughts went into this letter.

Your Dad and I have certainly been aware of the situation at Valley Home and do understand the problems you’ve had to face. We do realize you have the right to make up your own mind about what you want to do.

We realize that this independent living program has been quite successful with other disabled persons. We’re hoping that eventually such a program will be started here at home. The university is so far away.

But if you’re accepted in the school, since this is something you want to do, then this is fine with us. If not, maybe all of us could do something about finding a place that would be more for your needs than Valley Home.

We love you Norma,

Mom

I was relieved when I got the letter. I had already written my application. Was that an ordeal! I wonder if they ever had an application essay quite like mine:

Wow, here I am, Norma, writing an essay for application to your university. I can’t believe it—me being further educated at a university. If it weren’t for several people encouraging me, I would never be so bold.

Now let me tell you about myself. I was born May 3 … During my high school years at Valley Home, I was secretary for class meetings. I would take notes by hitting one key on the typewriter for each word, and then later go back and fill it in and type up the minutes. I adapted, but honestly, if I had those fifteen years of education to do over again I would not stand for being in special education the whole time.

It takes longer for me to get through classwork because I can’t write with a pen and I have to poke at the typewriter. But I feel so good when I complete the course and have a reasonable knowledge of the subject.

… By the way, whenever I have time, sometimes I just take the time, I love to play scrabble. During the five days it has taken to write this essay, I would much rather have been playing scrabble. But only playing scrabble is not what life is about.

To be honest with you, I am applying to your university for two big reasons. One, to finish my education in the field of writing … and two, to go through your physically disabled students residency program. I need to live in a more stimulated environment.

I’ll be ever grateful and honored to be accepted at your university.

Norma

Well, I was accepted. My only concern now is that I graduate before I am 65. On the nonacademic side, I love living on my own after 20 years in a home. You don’t have to tell anybody where you’re going or what you’re doing. At first it’s hard to get used to. You also have to take on all the responsibilities of housekeeping: having groceries in the house, paying your bills, going to the bank. Everything that was once done for you, you have to do yourself. When I moved into my first apartment and there was no toilet paper, then I really knew I was living on my own.

If I had to do it all over, I would be even more of a rebel than I was. If you’re living in an institution and you know you can do more with your life, get a rehab worker, a counselor at an Independent Living Center, get somebody, somebody, behind you, and get out. It’s worth it.

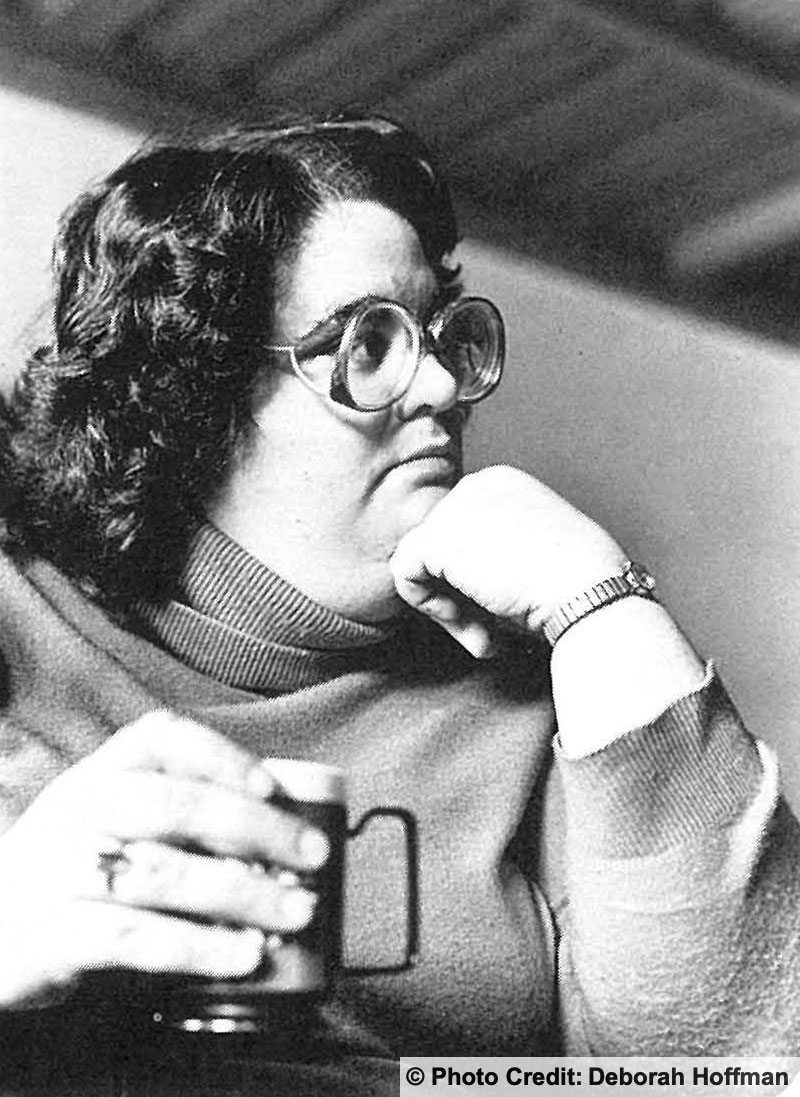

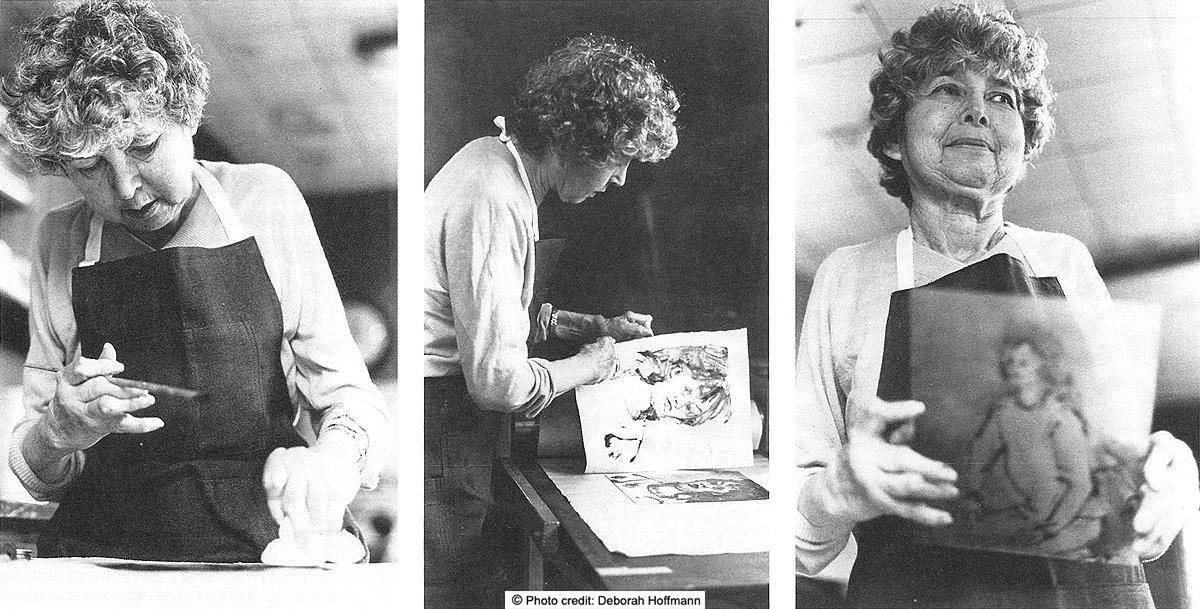

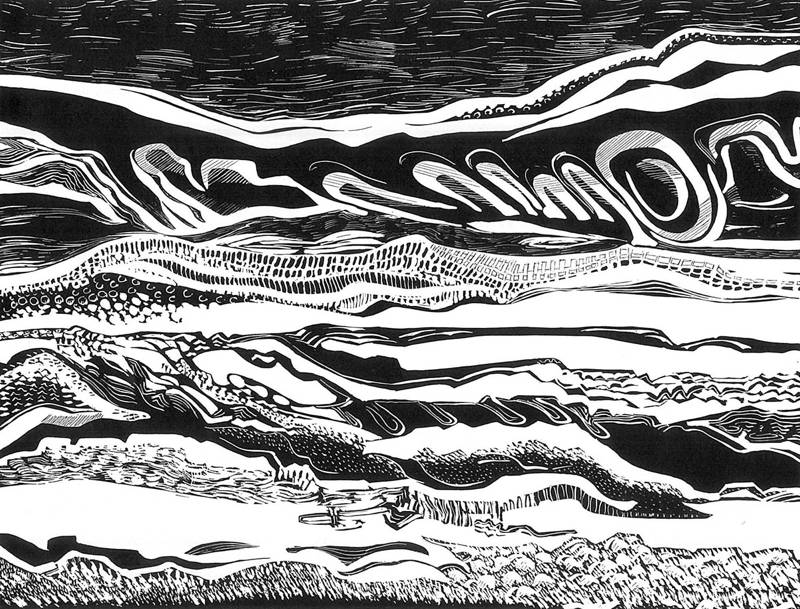

Virginia Rubin

Because I’m an artist who is disabled, whose hands, arms and shoulders are affected by rheumatoid arthritis, I have to improvise in my work and find other ways of doing things. For example, I have to work on a series of smaller things to make one big thing. I did a series of six paintings, all of a size I could handle myself, and then I put them all together to make a piece that was 16 feet long … that’s big.

Or if I can’t make a huge, broad stroke with a brush, I make tons of small ones.

My disability is progressive so, even now, I’m losing hand control of fine movement. All along I’ve found a way to paint, so I suppose that as long as I care to do something, I’ll find a way.

For example, when I went back for my master’s in studio art, after my kids were grown, I had to stop right in the middle of a semester for surgery. I was majoring in print making, had been a print maker for years. But, finally, after the surgery, the physical bulk of the materials involved—huge copper plates, big pans of acid—and the tiring steps of preparation got to be too much. It was too difficult. I was using a luggage carrier to get from one part of the school to another and offering people cokes to carry things for me.

So I experimented and found a different way of doing things. I started making monoprints which was fairly unheard of at the time. And I used materials that had rarely been used and which were very light—plexiglas instead of glass or copper plates. I used a paper that didn’t require a lot of steps of preparation.

You see, very early on in my life, when I was about eighteen, I decided that I would live to the max, that I would have an absolutely normal life. Whether or no, I wanted a marriage, a family, a career in the arts, and that’s what I have had. I’ve been lucky. Pain is a constant in my life, always has been. But in the interest of living, the pain became tolerable.

And I’ve always thought that was the prize—LIVING.

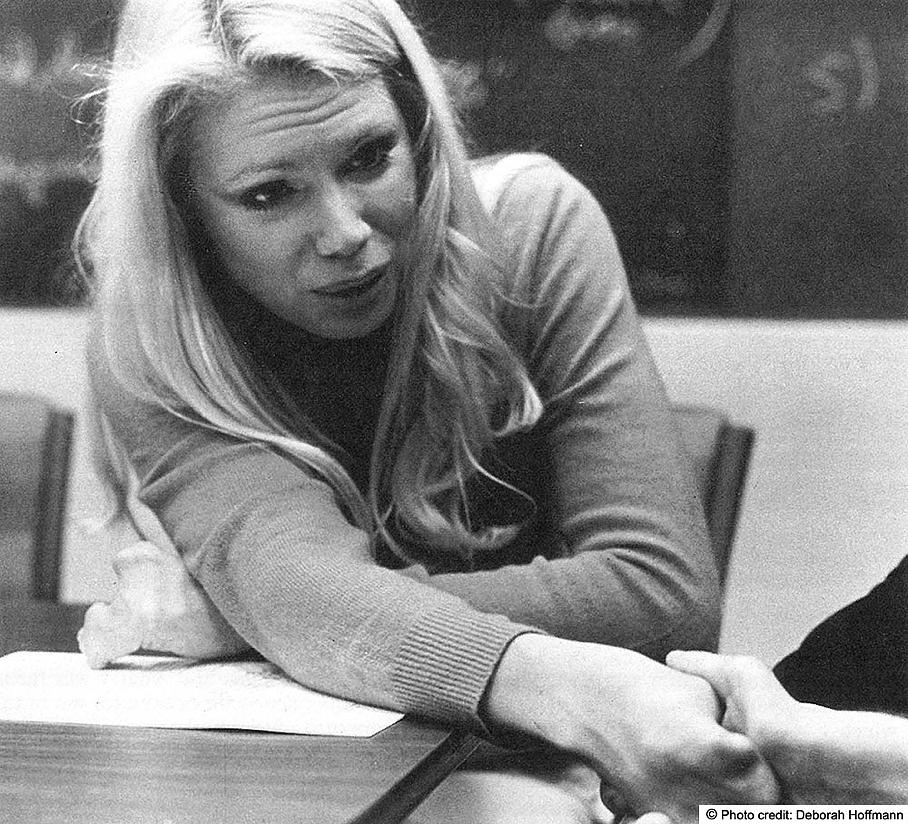

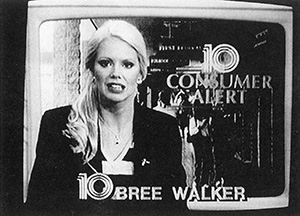

Bree Walker

I wanted to become a model in the first place because I wanted to refute everything they said in the fashion magazines about what perfection was, about what beauty was. It disgusted me, I knew I’d never see a model like me. I was born with syndactylism. Trying to fight all odds, I went into modeling. Luckily, I had the right face for the right cosmetic—an eye makeup—and the firm hired me without knowing I had anything wrong with my hands or feet. They were quite shocked when I walked in.

I was never allowed to do runway modeling and they kept me away from the press. I couldn’t wear the whole package, the high heels, the sheer stockings, the bright pink nail polish. I was a good head shot and that was it. The nights I felt fit to kill were the coldest nights, the nights I could keep my hands in my pockets and wear boots.

I only did the modeling to get through college where I majored in broadcasting. I landed a job as one of the first women disc jockeys at a radio station in Kansas City. The radio career helped validate my attitude about myself. It was a relief to succeed in something I did well.

For years in grade school and high school, I had been the class clown, using my disability to get people to laugh at me. I wasn’t a real comic so I only degraded myself. But I wanted to be liked, to be someone the guys would want to date.

When I was about sixteen, I discovered that a couple of the guys I had dated were calling me lobster claws behind my back. I was devastated for about a year. And then I decided I was going to start liking myself, and at the same time I became a liberated woman. I became an outspoken student activist with a strong drive for a career in the news.

So after my success in radio, I wanted to break into television.

I had been courting this TV station for a year. It was a network affiliate with a good reputation, especially in the news department. In the beginning, they wouldn’t even look at the video tapes I had of myself the standard way to audition in TV. Eventually, they did look and eventually they did hire me. Everyone felt it was a big risk.

At first on camera, I wore my prosthesis—very life like—looking hands which fit like gloves. I wore them on camera about two weeks. Wearing the prosthesis had been one condition for hiring me.

At first on camera, I wore my prosthesis—very life like—looking hands which fit like gloves. I wore them on camera about two weeks. Wearing the prosthesis had been one condition for hiring me.

After the first two weeks, my boss came up to me and said, “You’re improving so quickly but you’re not moving. Are you bothered by the fact that you’re wearing your gloves?” And I said, “Yes.” Then he said, “Take them off.” I was in seventh heaven. I thought I had finally made it.

But that reaction was nothing compared to my feelings about the first letters we got after we got rid of the gloves. A woman called me and said she had two sons who were born without arms. She’d been very unreconciled to it until she saw the show. She said I was an inspiration. I thought, this is hokey but I’m going to cry. I knew I had made it.

All along I’ve wanted recognition on camera. I wanted the world to encompass me and love me and say, “You’re OK. You’re pretty. We like you.” That was my motivating factor for being on television.

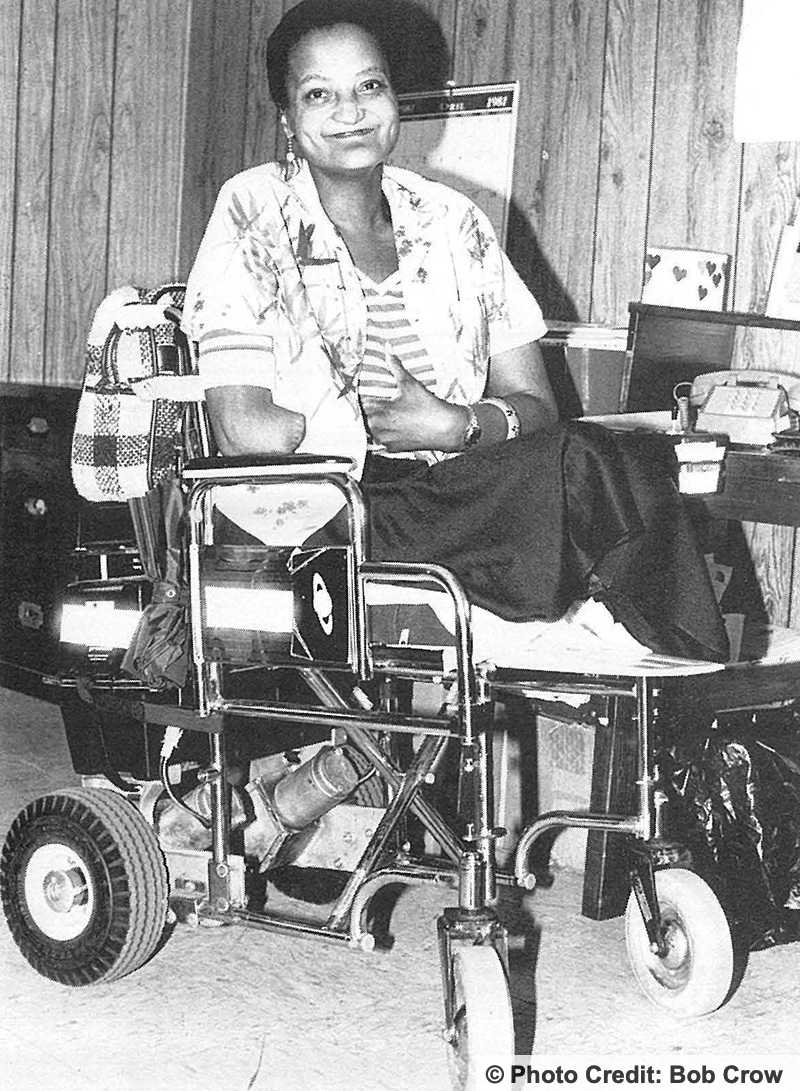

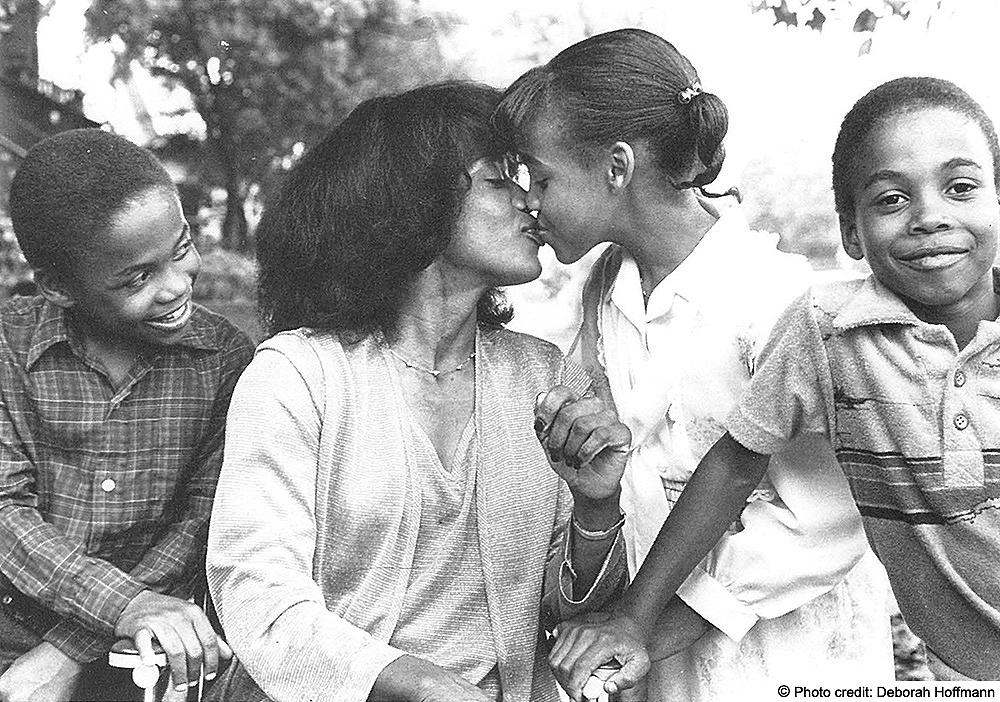

Re’gena Bell

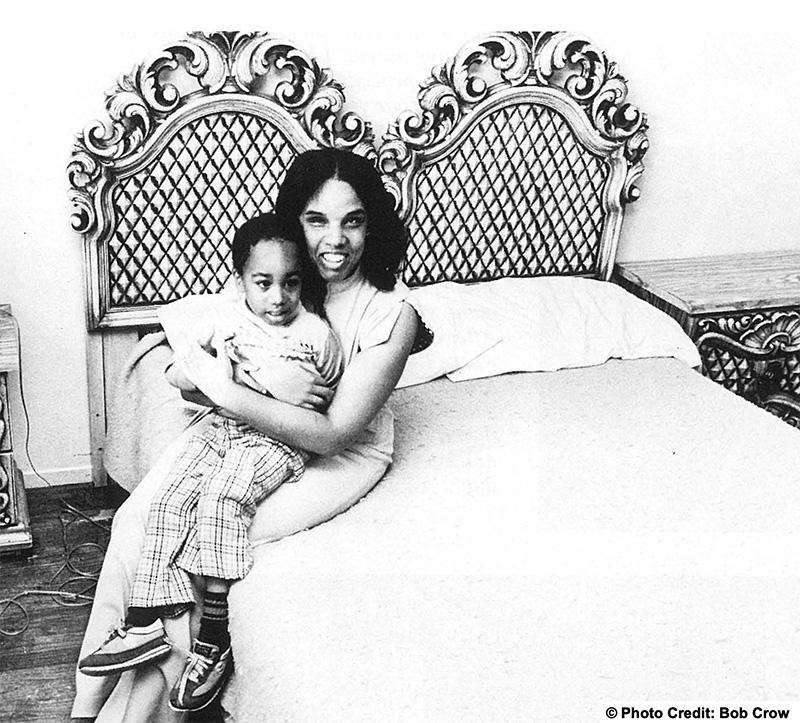

I was already the single mother of two-and-a-half-year-old triplets at the time of the accident that left me a quadriplegic. After I was shot, I had all kinds of people approaching me asking me to give up my kids. People said, “You’re not going to make it.” Every time somebody tells me I can’t do something, it gets me riled up to show them what I can do.

At the beginning of my recovery, I could barely speak. The kids pulled me through—yelling at them strengthened my voice! If it hadn’t been for them, I wouldn’t have made it. If I fell out of bed, the kids would pick me up. When they were still very small, and I was using a housekeeper, she was late one day and I needed clothes washed for the kids. I told them what to do—how to put the money in the machine, how to fold the clothes. They did it! Blew me away. My children are the closest people in my life.

And to all the people who told me I couldn’t do it: you were wrong. It was an effort after the injury, yes, but it was my life. Nobody could change it. If it was going to work I would have to make it work. If I failed, my children and I would fail together, and if I succeeded we would succeed together.

Conclusion

by Victoria Lewis, Ann Cupolo Freeman and Corbett Joan OToole

No More Stares is a book about possibilities: what other women with disabilities have done, what you could do. As you have seen, there are many choices today, many more than ten years ago. And there are more people around to help you decide on a plan for the future whether it’s for the next four months or the next ten years. You should try your parents, your school, your local independent living center or disabled student services. The resource guide at the end of the book will give you some good suggestions about where to go next.

Many of you are in school. Maybe you attend a school for disabled students in the city you live in. Perhaps you go to a state school or maybe you’re in a program to mainstream disabled students into a regular public school. You might be one of the few or the ONLY disabled student in your whole school! Or do you have a home teacher?

Whatever the situation, the unfortunate truth is that most disabled students do not receive as good an education as non-disabled ones. Maybe you don’t feel that’s true for you. But if you feel you’re not getting what you need, all is not lost. Because of many years of discrimination against disabled students, there are now federal laws that say schools have to give everyone an equal chance to get a good education.

So if they tell you that you can’t take a certain class because you’re handicapped or female, tell them it’s against the law. If you need more information on this, see the Resource Guide.

Even though there are possibilities, nothing happens by magic. We know it can be hard to find a job when you are disabled and a woman. Partly that’s because of the inferior education we often get, and partly that’s because of architectural and attitudinal barriers.

Still, for every different job you can imagine, some disabled woman is doing it. Some of us are scientists and computer programmers, some of us are counselors and teachers and social workers, some of us are maintenance and repair people. Some of us work at more than one job and are also mothers. Every one of us can do some kind of work. Don’t let anyone tell you differently.

The women in this book got their job skills in many ways, all of which are possibilities for you. Volunteering is a good way to learn about what you want to do. As a teenager you can try out many different jobs. One woman worked at the local Y, at a soda fountain, in a drug store, as a camp counselor, as a file clerk, as a telephone receptionist at school, as a babysitter, as a dog walker, etc.!

Most teenagers can’t wait to get away from home, to be on their own. And most of us are frightened when the day comes. For a disabled woman there are additional fears. Those big important questions arise: What about the help I need to get dressed and go to the bathroom? Who will read my mail to me and help me to pay my bills? What does moving out of a dependent situation into an inde- pendent one entail? Some people seem to be able to change their lives overnight and never blink. Others needs lots of time and support to make a small step towards independence. It doesn’t matter how long it takes you. It’s not a race. It’s your life and you can choose the pace that’s comfortable for you.

Remember: being independent doesn’t mean being alone. It means a chance to get out in the world on an equal footing with other people and live through all the good and bad things that make up a life. It can mean anything from a chance to work at McDonald’s to taking an art class, to riding a city bus, to falling in love. It can mean getting fired from McDonald’s, giving up art for mechanics, complaining about the crowded buses at rush hour, or falling out of love. And then back in again. In love with people or a new apartment or a job or a sports wheelchair. You name it! The important thing is, in your own way and at your own speed, to get out there.

Title Page

No More Stares

Coordinators and Managing Editors: Corbett Joan OToole and Ann Cupolo-Freeman

Author of “Anna’s Story”: Victoria Lewis

Interviewing and Editing: Victoria Lewis with contributions from Corbett Joan OToole, Ann Cupolo-Freeman and Lois Dadzie

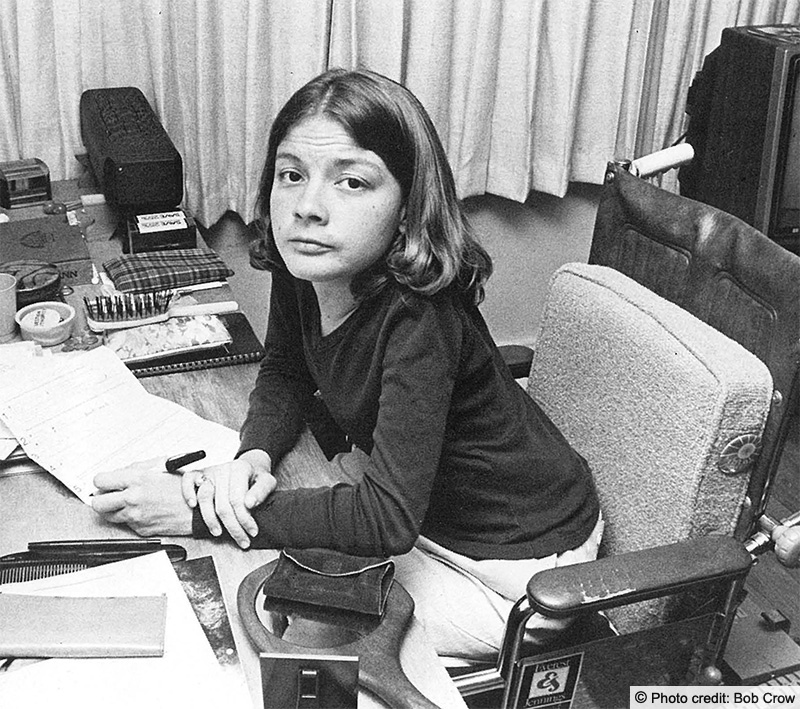

Editorial Design: Deborah Hoffmann

Art Director/Designer: Bob Crow

Researchers: Lois Dadzie, Melissa Lessard and Esther Reynolds

Editing Assistant: Deborah Ellis

Administrative Assistant: Jacqueline Norris

Research Assistance and Typing: Caryatis Cardea

DREDF Staff:

Executive Director: Robert Funk

Deputy Director: Mary Lou Breslin

Disabled Women’s Education Project Staff:

Coordinator: Corbett Joan OToole

Deputy Coordinator: Ann Cupolo-Freeman

Publications Coordinator: Melissa Lessard

Research Assistant: Lois Dadzie

Administrative Assistant: Jacqueline Norris

Typeset by turnaround, Berkeley

Printed by Inkworks, Berkeley

Cover designed by Bob Crow

Photo inset by Nick Allen

Copyright © 1982 by the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund. Inc.

3075 Adeline Street, Suite 210

Berkeley, CA 94703

All rights reserved. including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The contents of this publication were developed under a grant from the Women’s Educational Equity Act Program, Department of Education. However, these contents do not necessarily represent the policy of that agency or the endorsement of the Federal Government.

Permissons

Permission to reprint sections from the following books and publications is gratefully acknowledged:

A documentary film A LADY NAMED BAYBIE, a portrait of Baybie Hoover. Copyright © 1980, Martha Sandlin Productions, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Images of Ourselves, copyright © 1981 by Jo Campling, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., London and Boston.

See Me More Clearly, copyright © 1980 by Joyce Slayton Mitchell, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York and London.

Sexuality and Physical Disability by D. Bullard and S. Knight, St. Louis. Copyright © 1981 by the C. V. Mosby Company.

Rehabilitation Gazelle, copyright © 1977 by Gini Laurie, 4502 Maryland Avenue, St. Louis, Mo. 63108.

“Surviving Our Society with Its Limitations,” copyright© 1981 by off our backs, Washington, D.C.

The Independent, copyright © 1979 & 1980 by Center for Independent Living, Berkeley, Ca.

Sepia, copyright © 1970 by Sepia Publication Corp., Ft. Worth, Tx.

“American Sign Language,” BULLETIN, Vol. 11, No. 1&2. Copyright © 1980 by the Council on Interracial Books for Children, 1841 Broadway, NewYork, N.Y. 10023.

Quotes and photographs reprinted with permission. Copyright © 1974, 1975 & 1980 by Accent on Living, Bloomington, Ill.

Mainstream Magazine, copyright © 1978, 1979 & 1980 by AbleDisabled, Inc. San Diego, Ca.

I Don’t Just Cope—! Live! by Betty Medsger. Copyright © 1982 by Betty Medsger, Palo Alto, Ca.

Like It Is by Barbara Adams. Copyright © 1979 by Barbara Adams. Reprinted with permission of publisher, Walker & Company, New York.

All Things Are Possible by Yvonne Duffy. Copyright © 1981 by Yvonne Duffy. Published by A. J. Garvin & Associates, 720 East Ann Street, Ann Arbor, Mich. 48104.

Comeback, from pp. 2-21 & 137-138 by Frank Bowe. Copyright © 1981 by Frank Bowe. Reprinted by permission of Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., NewYork.

Deaf Awareness for Public Librarians copyright © 1975 by Alice Hagemayer, published at the D.C. Public Library, Washington, D.C.

Disability Our Challenge, copyright © 1979. Reprinted with per- mission of editor, John P. Hourihan. Funded by U.S. Bureau of Education for the Handicapped.

The Deaf American copyright © 1976. Courtesy of National Association of the Deaf, Silver Spring, MD.

Deaf Heritage, copyright © 1981 by Jack Gannon. Courtesy of National Association of the Deaf, Silver Spring, Md.

Reprinted courtesy of The Boston Globe, a quote from Lisa Thorsen, an article written by George McKinnon, Jan. 18, 1981.

Laurie, Ginny and Judy, reprinted from FEELING FREE by Sullivan, Brightman and Blatt, copyright © 1978, by permission of Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

“Taking Charge of Your Life: A Guide to Independence for Teens with Physical Disabilities.” Copyright © 1981, Parents Campaign for Handicapped Children and Youth, Closer Look, 1201 16th Street, N.W., Washington. D.C. 20036.

Disabled USA, Vol. 4 No.6, 1980; pp. 21 by Diane Lattin. Courtesy of The President’s Committee on Employment of the Handicapped, Washington, D.C.

Toward Intimacy by the Task Force on Concerns of Physical Disabled Women. Copyright © 1978 Human Sciences Press, NewYork.

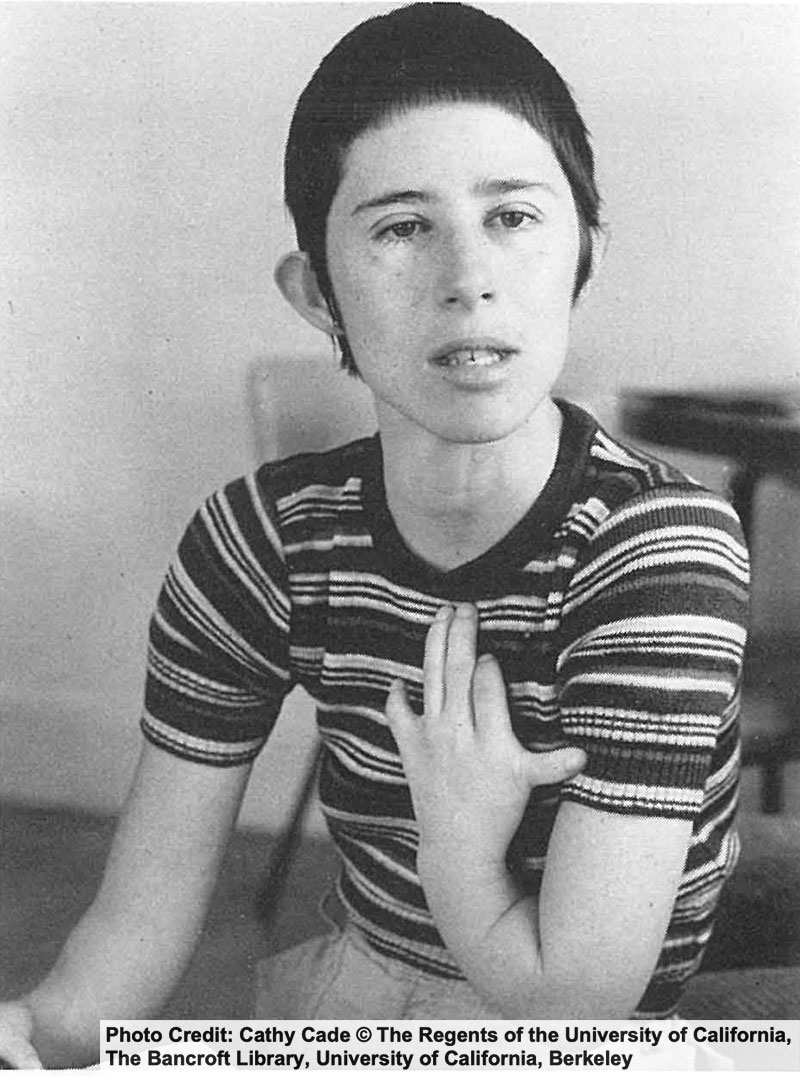

The Making of a Documentary Photographer by Susan Riess. Copyright © 1968 Regional Oral History Office, University of California, Berkeley.

Living in the Open by Marge Piercy. Copyright © 1976 by Alfred A. Knopf, NewYork, NewYork.

What Happens After School? A Study of Disabled Women and Education by J. Corbett O’Toole and CeCe Weeks. (San Francisco: Far West Laboratory for Women’s Educational Equity Communications Network , 1978.)

The Dream’s Not Enough: Portraits of Successful Women With Disabilities, Resource Guide by the Institute for Informational Studies. Copyright © 1981 Institute for Informational Studies, Falls Church,Va.

Design for Independent Living: The Environment and Physically Disabled People, by Raymond Lifchez and Barbara Winslow, © 1979 by Raymond Lifchez. New York: Whitney Library of Design, 1979 (hardback); Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982 (paperback).

Closing Thoughts

“Our wind blows on toward those hills we will never see.”

– from “On Castle Hill,” by Marge Piercy

Times do change and things are possible today that I wouldn’t have thought possible ten years ago. Who knows what the next ten years will bring?

– Toni, post polio

I feel so much love even though people do turn their heads and pretend I’m not there. It makes me angry sometimes but that gives me the drive to do something because I’m not alone. There’s a lot of disabled people out there.

– Re’gena, spinal cord injury

No self-pity, ’cause that’s out. I was told so often when I was young, “I DON’T WANT YOU, THEY DON’T WANT YOU, NOBODY’S GONNA WANT YOU, if you cause trouble nobody’s gonna want you.” At a certain age in my life, it dawned on me—well, I want me. If no one else on earth wants me, I do. When that came to me, that gave me courage and so I just proceeded on.

– Baybie, blind

I’m happy because I like to be a human being.

– Ann Marie, Down’s syndrome

I like to be treated the same as everybody else, so far as possible, and that’s pretty far! I’ve found that I can do more things than most people think I can. Maybe not everyone with a visual handicap gets around as much as I do. Most of them could, though, if they had the chance to learn and practice. I bet they want to. I know I want to. Because I like people. I like the world. And I think it’s going to like me!

– Antoinette, blind

You don’t have to have 100% of the world at your disposal. No one does. But what you have can fill up a whole life. The world is enormous. No one gets it all.

– Corbett, post polio

I get frustrated with the slowness of change, and the slowness of people to change. We’ve come a long, long way, but we still have a very lengthy journey ahead of us. I am amazed and angered at how few people see me as a person. I am a human being who happens to be blind, not a blind being who happens to be human. But it is astounding how few people understand that. I don’t think I will ever rest until they do- not just for me, but all of us!

– Eunice, blind

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all the women who shared their time and experiences during the past three years, thus inspiring me both personally and professionally. Thanks to the staffs of the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund and Berkeley’s Center for Independent Living (in particular Judy Heumann) for introducing me not only to many of these women but also to the philosophy of the independent living movement. Also thanks to Barbara Waxman and Tari Susan Hartman for their guidance in contacting the Los Angeles community and suggesting resources. The DREDF staff also provided the research and clerical backup without which this book would have eternally remained a good idea. It was a great pleasure to collaborate with Lois Dadzie, our non-flagging research head. Particular thanks to Katherine Corbett for conceiving the book along with its wonderful title.

My deepest gratitude to Deborah Hoffmann and Pam Mendelsohn for their enthusiasm, belief, criticism and love throughout this project.

I would like to make my own personal dedication of No More Stares to Virginia Rubin. Ginny didn’t live to see this book, but she was for me in the last months of her life a role model. A role model, first, of a successful woman artist who happened to have a disability and secondly, and more importantly, of a woman who had, by the time I met her, learned the difficult task of balancing passion, humor and faithfulness in her friendship and her work.

Victoria Lewis

There are people who made this book possible, people who gave this book direction, and people who made this book fun to do.

The people who made this book possible are: Leslie Wolfe, Director of the Women’s Educational Equity Act Program, who believed that equality should be for all persons, not just those who are white and able-bodied; Robert Funk, Executive Director of DREDF, who created an agency committed to changing America’s misdirected policies for the disabled; and the disabled girls and women who responded enthusiastically to No More Stares.

Many people gave us help and direction: Merle Frosch! and Barbara Sprung of the Non-Sexist Child Development Project, NewYork City; Mary EllenVerheyden at the Equity Institute, Bethesda, Md.; Lori Grey, student at the University of California, Berkeley; Carolyn Vash, Institute for Information Studies, Falls Church, Va.; Pam Mendelsohn, Cal State University at Humboldt; and our families, who laughed and cried with us through it all. Thanks especially to Jennifer Luna Bregante for her inspired suggestions and her continuing belief in our ability to carry this book from idea to completion.

The staff of DREDF and the No More Stares staff made this book fun to do. Throughout this process of putting a book together, a first for most of us, we found that no matter how distressing or overwhelming the book seemed at times, one of us would see a funny side to the situation and we’d all end up laughing.

When we worried over not enough money, one of our kids came up with the dough, courtesy of her “Monopoly” game. As the deadlines closed in and we fretted about time, someone would call an “It’s about time for a break” party and we’d all laugh and relax.

We learned that though individually we had limited knowledge of bookmaking, collectively we could resolve every situation.

Corbett Joan OToole

May, 1982

Berkeley

Preface Continued