May 20, 2020

via Electronic Submission to regulations.gov

Seema Verma

Administrator

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Department of Health and Human Services

Attention: CMS-2418-P

P.O. Box 8016

Baltimore, MD 21244-8016

Re: Comments on Proposed Rule: Preadmission Screening and Resident Review CMS-2418-P

Dear Administrator Verma,

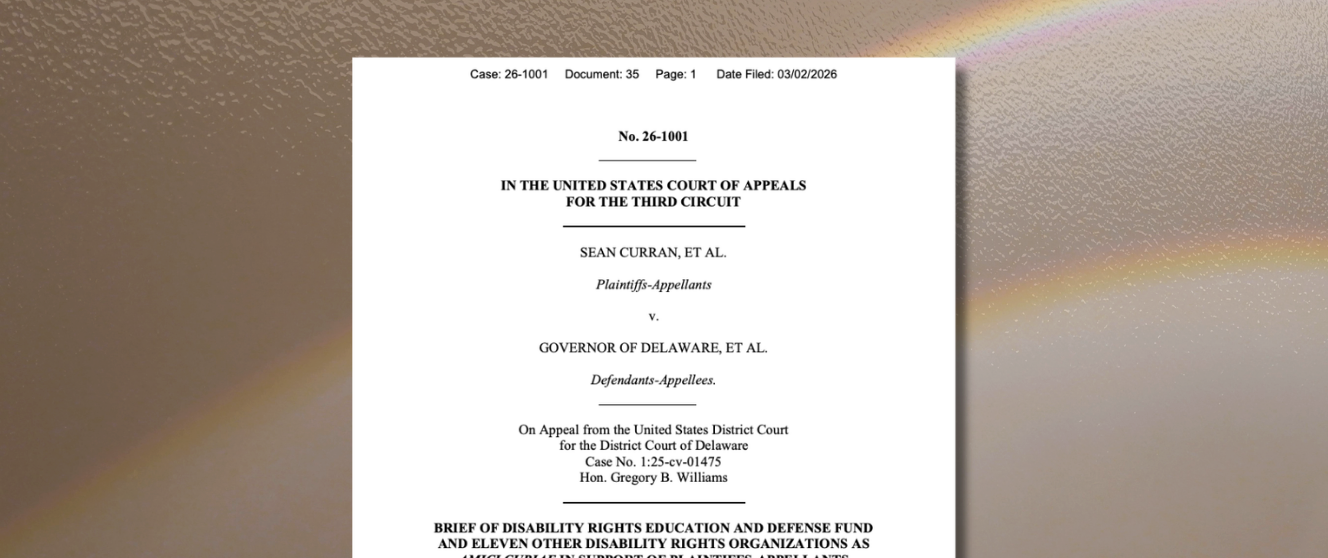

The Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund (DREDF) appreciates the opportunity to provide comment on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) proposed rule on Preadmission Screening and Resident Review, CMS-2418-P. DREDF is a national cross-disability law and policy center that protects and advances the civil and human rights of people with disabilities through legal advocacy, training, education, and development of legislation and public policy. In the more than 40 years that have passed since our founding, we have persistently fought for the right of people with disabilities to be fully integrated within all aspects of community life, including the receipt of accessible and equally effective healthcare in the community rather than in segregated nursing homes. Following the Supreme Courts 1999 Olmstead decision, we co-counseled a case on behalf of residents at Laguna Honda Hospital, one of the largest remaining skilled nursing facilities in the country, who wished to receive services and supports in the community rather than an institution.

The Preadmisssion Screening and Resident Review Process (PASRR) was developed to identify and assist individuals like our Laguna Honda clients achieve their goal of avoiding spending their entire lives in an institution. The profound desire for deinstitutionalization shared by so many disabled persons did not arise with COVID-19, but the pandemic has sharpened the urgent need for deinstitutionalization and threatened the lives of residents with disabilities, all too many of whom have had their fear of ending their days in a nursing home come true with swift brutality. As stated in the proposed rule, it is past time for PASRR to be evaluated and updated, but DREDF asks CMS to reconsider its current draft of the proposed rule in light of the great health risks posed by the coronavirus in long-term care facilities, to ensure that the PASRR diverts individuals with mental illness (MI) and intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) as much as possible, and maximizes the discharge of such individuals to the community with appropriate community-based services and supports.

I. The Need for Updating PASRR

DREDF has closely followed COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death rates as reported by states and federal agencies. We have noted with dismay the release of more granular information about where infections and deaths occur: as of May 14, 18 or more states report 50% or more of COVID-19 deaths have occurred in long-term care facilities, with Minnesota, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island each reporting over 75% of deaths occurring in LTC facilities. Only Nevada, New York, and D.C. report fewer than 24% of deaths in LTC, and 15 states have not yet reported location-specific numbers.[1] Based on an analysis of demographics and LTC use in the mostly rural non-reporting states, a report from the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity (FREOPP) estimates nationally, the share of fatalities from nursing home and residential care facilities is 40 percent, and 51 percent outside of New York State. The report concludes it would appear that elderly individuals who do not live in nursing homes may be at a somewhat lower, while still significant, risk for hospitalization and death due to COVID-19, and recommends policy responses that reorient away from younger and healthier people, and toward the elderly, and especially elderly individuals living in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities.[2]

Nursing home coronavirus infection and death rates concretely confirm what the disability community and disability advocates have long asserted: institutionalization is life-taking. The COVID-19 pandemic is only the latest in a long line of legal, social, and medical reasons to minimize the institutionalization of people with and rebalance Medicaid. Against this backdrop stretching back even before the Olmstead decision, the primary purpose of the PASRR regulations and program is to ensure that individuals with MI or IDD are not unnecessarily admitted to nursing facilities, or if they are admitted, they are given every opportunity to receive services that will equip them to return to the community and leave a segregated setting. Since the PASRR regulations were first enacted, we have had the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the aforementioned Olmstead decision, guidance from CMS and the Administration for Community Living (ACL) on implementation of an integration mandate for people with disabilities and older persons, specific provisions and funding enacted in the Affordable Care Act that incentivized state rebalancing toward home and community-based services (HCBS) and away from nursing home care, and multiple professional healthcare standards that emphasize the benefits and greater effectiveness of community-based treatment and supports for people with MI and IDD. The PASRR standards should therefore be strengthened to better support diversion of older and disabled persons away from nursing homes, and assure discharge of nursing home residents wherever and whenever possible, Instead, the proposed rule seems to undermine community integration of people with disabilities in myriad ways.

II. PASRR and Informed Choice

For maximum effectiveness, the PASRR preadmission screening (Level I) and evaluation (Level II) should cast a broad net to prevent unnecessary admissions to nursing facilities. PASRR evaluations should be applied generally to every person with MI or IDD that could be admitted to a nursing facility level of services to avoid the consequence of failing to divert anyone, at the earliest possible opportunity, away from the nursing home setting who would be better served in an integrated alternative setting. By giving States the option to characterize readmissions, nursing facility transfers, acute hospital discharges, and provisional admissions as not falling within the preadmission category, the proposed rule creates significant gaps through which individuals fall outside of the PASRR process, including those who are admitted for respite, crisis or protective services, and convalescent care.

Even before the COVID-19 crises, nursing facilities in some estates such as Texas and Illinois avoided applying preadmission PASRR evaluations to the vast majority of admissions of people with IDD. With the COVID-19 emergency, CMS has authorized provider flexibilities such as hospitals without walls[3] which even as they facilitate options for housing and treating hospital patients who do and do not have COVID-19, also increase those who are brought within the physical purview of nursing homes during a time of potentially rapid and changing patient status and treatment needs. California, for example, requested Section 1135 Waiver flexibilities pursuant to COVID-19 related needs and issued a guidance on how hospital services may be administered in alternate patient settings such as skilled nursing facilities, intermediate care facilities, and psychiatric residential treatment facilities.[4] Once the treatment period ends, there will be individuals within the institutional settings who may or may not meet admission criteria during a period of possible extended recovery; it is unclear what procedurally will happen to these individuals who are not physically in a hospital but who are still in need of medical care, even if it is not intensive care. If these are individuals with MI or IDD facing a preadmission situation, they should be unquestionable provided with a PASRR evaluation. Conducting such an evaluation months, or even mere weeks later, drastically reduces the opportunity for return to the community as housing, and formal and informal supports and services may be lost in the interim, prompting a far greater risk of long-term institutionalization. The proposed rules substantially undermine the diversion goals and elements of the existing PASRR program, and particular in light of coronavirus treatment flexibilities that may bring people with disabilities into LTC facilities.

Moreover, the proposed rule sharply limits the PASRR Level II evaluation with respect to placement in an alternative community setting. The proposed rule authorizes the admission of individuals who do not have a currently available community option, even if the person could be served in an integrated setting or better served in the community. This language makes the individuals rights entirely dependent upon the happenstance of waiting lists, the states existing funding and planning for community-based services, and the ability and inclination of LTC facility employees to keep themselves fully informed of all community-based options. While the proposed rule requires that states provide individuals (or guardians) information about community options, there is no requirement for informed choice, no specification of the type, amount, or frequency of such information, and, contrary to Olmstead, an assumption that institutionalization is appropriate unless the person expresses a preference for community placement, instead of an assumption that community placement is appropriate unless the person opposes such placement. This is particularly inappropriate for individuals with MI and IDD who may need plain English, additional time, and repeated opportunities to ask questions to fully absorb their community-based living and treatment options, especially if this information is given after an individual has already been in an institutional setting for any length of time.

III. Specialized Services

Third, the proposed rule significantly diminishes the specialized services that must be provided to persons with IDD or MI. It substantially restricts the assessments used for determining if specialized services are needed, focusing almost exclusively on ADL and IADL assessments instead of a broad range of social, vocational, educational, and communication areas, as in the current regulations. It allows a state to drastically limit the type of specialized services that will be provided in nursing facilities and eliminates any standard for determining what services should be provided, despite the mention of person-centered care. In addition, the proposed rule fails to detail the kind of special training that should be required of nursing home PASRR evaluators. For individuals with MI and IDD, and particularly for individuals who may have multiple disabilities that include MI and IDD, staff and professionals cannot be allowed to rely on common assumptions and stereotypes about who could benefit from community placements and their capacity to do so.

Finally, we wanted to particularly oppose the proposed rules elimination of evaluation criteria for individuals with traumatic brain injuries (TBI), particularly since a TBI that occurs before age 22 is characterized as a developmental disability or related condition. The mere chance of when the TBI occurs determines whether the PASRR rules apply which is completely illogical and unfair. During DREDFs Laguna Honda litigation, I represented an individual plaintiff who experienced a TBI as a young man when he was severely beaten while picking up his young daughter from childcare. My client spent several decades at Laguna Honda, and despite experiencing very high levels of psychological and physical institutionalization, he never gave up on his expressed desire to return to living in the community. However, when the chance of a community placement came up through the litigation, he came to the conclusion, in consultation with his children, that he could not return to the community unless and until he could walk again, even though he had been a wheelchair user for many years. My client should have had full access to PASRR evaluations that would have given him a fully informed choice, as well as specialized services that included training on ADLs/IADLs, community living skills, safe judgment, life management, and working with personal care assistants that would prepare him for a return to the community. He did not have this access.

For all of the above reasons, and particularly given the deadly consequences of nursing facility admission during the COVID-19 pandemic, DREDF strongly recommends that CMS reconsider the proposed rule, and substantially revise it to remove its current institutional bias, aligning it with prior CMS Guidance and directives from Congress and the Supreme Court on prioritizing integrated community placement

Thank you again for the opportunity to comment on this important rule. Please feel free to contact me with any questions or concerns about the above.

Sincerely,

Silvia Yee

Senior Staff Attorney

[1] Kaiser Family Foundation, State Policy and Policy Actions to Address Coronavirus, at https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/state-data-and-policy-actions-to-address-coronavirus/. Updated as of May 14, 2020.

[2] Girvan, Gregg, Nursing Homes and Assisted Living Facilities Account for 40% of COVID-19 Deaths, at https://freopp.org/the-covid-19-nursing-home-crisis-by-the-numbers-3a47433c3f70. May 7, 2020.

[3] See CMS, Additional Background: Sweeping Regulatory Changes to Help U.S. Healthcare System Address COVID-19 Patient Surge Fact Sheet, at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/additional-backgroundsweeping-regulatory-changes-help-us-healthcare-system-address-covid-19-patient. March 30, 2020.

[4] Department of Health Care Services, Provision of Care in Alternative Settings, Hospital Capacity, and Blanket Section 1135 Waiver Flexibilities for Medicare and Medicaid Enrolled Providers Relative to COVID-19, at https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/Documents/COVID-19/CMS-Blanket-Waivers-4-21-20-Rev.-Ambulance.pdf. April 22, 2020.