Download the PDF

Download the .doc

Content Warning

This report mentions or discusses ableism, disablism, child abuse, death, policing, racism, self-harm, sexual assault, suicide, and violence. This report also includes detailed stories of death and harm resulting from incarceration.

A Note About Language

This report uses a capital “D” for Disabled people in recognition of disability as an identity and culture. We acknowledge that not every person who experiences disability identifies with the disability community in this way.

DREDF currently uses person-first language and identity-first language interchangeably. Continuing the evolution toward person-centered language (both identity-first and person-first), in this series of reports, when referring to the disability community, unhoused people, and people who are incarcerated or formerly incarcerated, we use terms that emphasize personhood rather than status, diagnosis, or condition, e.g., “people experiencing mental illness” rather than “the mentally ill.”

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund (DREDF) for the opportunity to create this report. In particular, I am grateful for the support, input, and feedback from Carol Tyson, Mary Lou Breslin, Micah Rothkopf, Silvia Yee, Tina Pinedo, and Tom Olin. I also want to recognize the legacy and accomplishments of the late Marilyn Golden for her lifelong commitment to advancing disability policy.

Executive Summary

In this report, we invite readers to explore the historical, racialized, disablist, and political economic contexts of mass incarceration, including the ways that incarceration has expanded beyond prisons, jails, and correctional supervision in the 21st century. As well, publics often think of incarceration narrowly, such that they make invisible the containment of Disabled people in institutional and extracarceral systems. This report is in part a corrective and counterpoint to policy papers on disability and criminal legal reform published by non-disability advocacy and mental health advocacy[1] organizations in recent years. Because the ideologies of eugenics, ableism, and disablism are thriving in the 21st century, disability is often used as a rhetorical frame arguing for the restriction of carceralism for certain groups and its expansion for others. Mass incarceration in the 21st century includes physical confinement, but also accounts for the rapidly expanding, technocratic industries of e-carceration and psychotropic incarceration. Our conceptions of physical confinement must go beyond prisons and jails, and include detention centers, psychiatric hospitals, nursing homes, and residential treatment facilities. One cannot replace the other. Recognition of incarcerated people must similarly be expanded to include detained immigrants, people under electronic monitoring and surveillance, and people experiencing involuntary psychiatric commitment.[2], [3] Black people and Indigenous people continue to be disproportionately impacted by policing and carceralism, particularly in the increased criminalization of poverty, houselessness, and mental illness, and the ways that these statuses intersect with racism and disablism.

Private Equity

Though the average person may have no knowledge of or experience with private equity investing, almost every person in the United States has been impacted in some way by private equity’s encroachments into healthcare, education, retail, housing, and other sectors that provide essential services to the public. Private equity’s leveraged buyouts have resulted in millions of jobs, pensions, homes, and lives collectively lost over the past four decades. In the healthcare industry, including correctional healthcare, private equity ownership has been linked to tens of thousands of preventable deaths in congregate care settings, jails, and prisons.[4] The two largest providers of correctional healthcare services in the United States, YesCare and Wellpath, are both owned by private equity firms. Despite thousands of lawsuits filed against these companies within the past decade, they continue to retain, renew, and win contracts with hundreds of city and county governments across the country. In many cases, private equity firms that profit from physical incarceration also profit from alternatives to incarceration, especially through their investments in surveillance tech.

A Lack of Transparency

A lack of transparency, record keeping, and publicly available data create persistent barriers for researchers, journalists, advocates, and policymakers to document trends and incidents of abuse and neglect in prisons, jails, and detention centers. There is no national database tracking the deaths that occur in every prison, jail, and detention center, or the number of complaints and lawsuits filed against each facility. Public records requests can be costly, and state and local governments may be slow to respond or can restrict access to this information. Private equity similarly operates under a veil of secrecy that allows firms to evade government regulation and public accountability. Because private equity ownership is often hidden behind multiple business structures, with control of management and property split among different sub-entities, it is difficult to hold private equity firms accountable through litigation, let alone to grasp the true extent of private equity’s involvement in mass incarceration and its expansion.[5], [6]

Correctional Healthcare

There are currently no federal laws that establish minimal standards of care at correctional facilities, and there have been no academic studies comparing the quality of privatized correctional healthcare to government-provided services. A recent study by Reuters analyzing data from over 500 large jails found that out-contracted correctional healthcare was associated with 18 to 58 percent higher risk of death for people incarcerated at those facilities.[7] We conducted our own analyses using the Reuters data and found that the mortality rate at jails with publicly managed healthcare decreased 2.4 percent from 2015 to 2019, while the mortality rate at jails that contracted out healthcare to private companies increased 20.2 percent in that same time period. For all jails, the mortality rate has increased about 70 percent since 2008.[8]

From Medicalization to Criminalization[9]

In the introductory section of this report, we provide some background information on the disproportionate numbers of Disabled people and racialized and minoritized people, particularly Black people, impacted by mass incarceration, including alternatives to incarceration. We also describe the political economy of mass incarceration, which is a principal lens through which we map and contextualize the activities of private equity in this report. We argue that prison policy in the United States is a form of wealth redistribution for mostly white, male constituents who benefit from the carceral bureaucracy’s expansion.

In part one of this report, we discuss the history of mass incarceration as a racialized project of criminalization, disinvestment, and disenfranchisement of Black people. We also argue against the “Prisons and jails are the new asylums” fallacy, which has been propagated and perpetuated by the mainstream media, and we caution against deceptively alluring “alternatives to incarceration” that appeal to popular misconceptions of mental illness as a precursor to crime, and which expand rather than replace systems of physical confinement.

In part two, we discuss the modern history of immigration detention as an expansion of mass incarceration, and how the securitization of immigration in the decades after 9/11 reframed immigrants as an internal security threat and criminalized undocumented immigrants as permanent outsiders inside the borders of the United States. It’s also not a coincidence that the economy and immigration were among the most pressing issues for voters in the 2024 presidential election, giving the edge to Donald Trump, who has pledged to intensify mass deportation at an unprecedented scale once he retakes the White House. However, it is vital that we understand the criminalization and scapegoating of immigrants as a racialized project that has long preceded the Trump administration, with the complicity of both political parties.

In part three, the final section of this report, we tie together the issues of racism, disablism, and the political economy of mass incarceration by focusing on private equity’s role in manufacturing mass housing insecurity and the subsequent profiting off of false solutions to houselessness, including medicalization, criminalization, surveillance, and incarceration of unhoused people. Understanding these interconnections is important, as a post-election NBC News analysis reveals that Trump had some of the largest electoral gains in 2024 compared to 2020 in counties that experienced the most challenging housing markets.

For forty years, politicians have repeatedly victim-blamed, scapegoated, and criminalized unhoused people, but the problem of mass housing insecurity remains entrenched in large cities across the country, mainly because politicians refuse to tackle its root problems—unaffordable housing and rampant income inequality. While it’s important to recognize that houselessness is a housing problem, however, we also ask readers to be wary of homeless advocates whose main argument boils down to “Not all homeless people are mentally ill.” In our advocacy efforts, it is important that we not further marginalize and stigmatize one group for another. It is important not to invisibilize, pathologize, or victim blame the significant subset of unhoused people who are disabled or experiencing mental illness, which can be a lifelong identity or impermanent response to precarity and living on the margins of society. As the historian and disability scholar, Douglas C. Baynton, has argued, “This common strategy for attaining equal rights, which seeks to distance one’s own group from imputations of disability and therefore tacitly accepts the idea that disability is a legitimate reason for inequality, is perhaps one of the factors responsible for making discrimination against people with disabilities so persistent and the struggle for disability rights so difficult.”[10]

Introduction

In her seminal book, The New Jim Crow,[11] Michelle Alexander states that a contemporary analysis of mass incarceration must go beyond a mere accounting of the staggering numbers of Americans in prisons and jails. We must account for the twice amount of people under community supervision (probation and parole),[12] and we must acknowledge the lifelong impacts of being marked as “criminal,” which create a vicious cycle of poverty and alienation. A critique of mass incarceration must also explain the reduction in the nation’s prison populations that occurred during the past decade simultaneously with an explosive expansion of immigration detention and mass deportation. For example, tracing the history of immigration enforcement in the United States, Hernández (2011) shows how the political and racialized construct of “illegal alien” was built up and codified in successive layers of federal laws beginning in the 19th century, culminating in today’s permanently criminalized and excluded caste of undocumented noncitizens.[13] This occurred in parallel to the creation of a caste of permanently criminalized and confined Black Americans that officially began with the United States’ War on Drugs, though in effect continued a historical pattern of legalized alienation and exploitation of Black Americans originating in slavery and extending through the Black Codes of the 19th century, and the Jim Crow laws that followed.[14], [15]

This story of permanent exclusion for one group and permanent containment for another is an oversimplification, but provides a striking sense of the sheer and terrible expansiveness of mass incarceration in the United States. As a step towards completing this picture, Liat Ben-Moshe observes that disability as a frame for analysis is often missing in contemporary critiques of mass incarceration despite being central to its history, rhetorics, and political and economic construction.[16] The historian, Douglas Baynton, notes that the attribution of disability to connote defect or deficiency has been weaponized throughout United States history against marginalized groups, including immigrants and women, to justify their disenfranchisement, discrimination, exclusion, and of course, confinement. The earliest immigration laws, for example, excluded foreigners who were labeled as “convicts,” “lunatics,” “idiots,” “imbeciles,” “epileptics,” “beggars,” “feeble-minded persons,” and “those liable to become public charges.”[17], [18], [19] “While disabled people can be considered one of the minority groups historically assigned inferior status and subjected to discrimination,” Baynton writes, “disability has functioned for all such groups as a sign of and justification for inferiority.”[20] It has therefore been incumbent upon all these marginalized groups throughout history to deny disability or difference, or to assert their likeness or proximity to whiteness and cisheteronormative behavior in order to gain political power, rather than question the categorical denigration of disability as an attribute connoting defectiveness or deserving of exclusion.

Hence, when disability is discussed in critiques of mass incarceration, it is often framed through a medical and pathologizing lens, as “something in need of correction” rather than “a nuanced identity from which to understand how to live differently, including reevaluating responses to harm and difference.”[21] This medicalization of disability serves to legitimize carceralism in all its present forms by manifesting the construct of the “deviant, criminal mind” in need of correction, punishment, or containment that critics of mass incarceration otherwise assert to be a fiction.[22] In other words, most critiques of mass incarceration begin and end with the proposition that specific marginalized groups are not impaired and therefore do not deserve to be incarcerated, without questioning or only minimally challenging the fallacy that Disabled people need to be institutionalized, medicated, or incarcerated for their safety or the safety of others, whether in prisons, jails, psychiatric hospitals, residential treatment facilities, or through psychotropic restraint. Disabled people, especially people experiencing mental illness, are the current manifestation of the “monstrous other” in need of containment.[23] This is dangerous, because Disabled people exist among every identity, class, and status, and because the fallacy establishes disability, and mental illness in particular, as a discursive object with which elites can (and do) argue for the expansion of the carceral state across practically any category of people, but mostly against poor, racialized people, e.g., by loosening the criteria for coercive mental health intervention. Imani Barbarin has said that “blaming violent behavior on mental illness only excuses white people while criminalizing black people.”[24] Talila A. Lewis, the founder of HEARD,[25] observes, “disability is one of the most fluid and complex marginalized identities… In fact, ableism has been used for generations to degrade, oppress, control, and disappear disabled and non-disabled people alike—especially those who are Black/Indigenous (e.g., scientific racism). Relatedly, all oppression is rooted in and dependent on ableism—especially anti-Black/Indigenous racism.”[26]

Following historical patterns, we can anticipate that the expansion of the carceral state through ableist impulse and rhetoric will most severely impact those who live at the intersections of disability, poverty, and racial marginalization. Policing is “opportunistic and predatory,” Kimberly Jones writes, “They brutalize a bunch of poor people because they know they are economically disadvantaged and do not have the financial power to fight back.”[27] Law enforcement also has a history of targeting and entrapping racially marginalized people with intellectual, developmental, and psychosocial disabilities who live in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities—a deplorable practice that should be considered a human rights violation. As Human Rights Watch reports, during the “War on Terror,” law enforcement agents and their informants “often chose targets who were particularly vulnerable—whether because of mental disability, or because they were indigent and needed money that the government offered them.”[28] Approximately 30 percent of cases reviewed by Human Rights Watch involved government agents or informants targeting, grooming, and cajoling a Disabled person and providing the material support to commit a terrorist act. Again, we see how the national security state and the criminal legal system use Disabled bodyminds as discursive objects for their expansion and as exploitable objects for their profit.

As the scholar, Ruby Tapia, recently observed at a symposium at University of Michigan, the carceral state is more than its prisons and jails; it’s a system of “logics, ideologies, practices, and structures, that invest in tangible and sometimes intangible ways in punitive orientations to difference, to poverty, to struggles to social justice and to the crossers of constructed borders of all kinds.”[29] This system includes surveillance, policing, civil detention, probation, and diversion programs, as well as psychiatric forms of incarceration, including institutionalization and psychotropic restraint. As this report will make clear, the firms that are invested in prisons and jails are the same firms invested in immigration detention and alternatives to incarceration, including expansion of mental health courts. But, neither must a focus on political economy and the role of private prison companies erase the fundamental role of ideology, including white supremacy and eugenics, in establishing and maintaining mass incarceration.[30] As Ijeoma Oluo writes, “Health care discrimination, job discrimination, the school-to-prison pipeline, educational bias, mass incarceration, police brutality, community trauma—none of these issues are addressed in a class-only approach.”[31]

Michelle Alexander blends racial and political economic analyses of mass incarceration, and demonstrates how these strands can be mutually constitutive, writing that “politicians in the early years of the drug war competed with each other to prove who could be tougher on crime by passing ever harsher drug laws—a thinly veiled effort to appeal to poor and working-class whites who, once again, proved they were willing to forego economic and structural reform in exchange for an apparent effort to put blacks back ‘in their place.’”[32] Therefore, using an intersectional lens and the frameworks established by the aforementioned scholar-activists, including Michelle Alexander and Liat Ben-Moshe, as well as Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Alec Karakatsanis, and Marta Russell, we describe the ways that racism, disablism, and political and economic forces have shaped and expanded mass incarceration for their profit and to the detriment of marginalized communities.[33]

As Upton Sinclair famously said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”[34] In a political economy of mass incarceration, readers should become familiar with both the specific and tangible ways that private equity firms and other investors profit from carceral systems and rhetorics, and the more high-level and practically invisible ways that private equity firms shape mass incarceration through lobbying and other outsized political and economic influence. Although racism and eugenics play an indubitable part in mass incarceration, and although private equity firms are not the sole villains in this story, their role here—as in other industries where private equity has taken root—is important as it represents in many ways the peak of capitalism, naked avarice, and unabashed political self-interest.

Race, Disability, and Incarceration

In 2021, Clifford Farrar, a 51-year-old Black man with diabetes, died at the Stafford Creek men’s prison in Aberdeen, Washington, just several months after arriving at the facility. Farrar ran out of insulin supplies, which had previously been covered by his medical insurance. Prison medical staff repeatedly rejected his request for new supplies of insulin for his insulin pump, and Farrar eventually succumbed to hypoglycemia. He died shortly after his body was found, collapsed by the prison phones, perhaps trying to reach out one last time for help.[35]

The United States has the third largest population in the world, but holds more incarcerated people than any other country. There are currently 1,932,000 people incarcerated by the United States in prisons, jails, immigration detention centers, and under civil commitment.[36], [37] Between 40 and 66 percent of the state and federal prison population is disabled—that’s approximately 511,600 to 844,140 Disabled people who are incarcerated, just counting people in prisons.[38] Disabled people are overrepresented in both prisons and jails across almost every type of disability, including visual, hearing, physical, and cognitive,[39] substantiating critiques of the pervasive criminalization of disability through its interaction with socioeconomic factors such as poverty, housing, unemployment, and education.

Although Indigenous Americans and Black Americans report the highest prevalence of disability in the general population, white people were the most frequent group to report disability in the jail and prison populations.[40], [41] This suggests that disability by itself is markedly criminalized in the United States, and a disability lens could be constructively employed when examining the disparities experienced by Black people and Indigenous people in the criminal legal system, specifically through the ways that racism intersects with disablism for multi-marginalized people.[42], [43], [44], [45], [46] For example, according to one survey study, Disabled white people are 12 percent more likely to be arrested than nondisabled white people by their late twenties, but Black men have a 25 percent higher risk of being arrested. Disabled Black men have a 38 percent higher likelihood of being arrested than nondisabled white people.[47] Since 2015, Black people have been killed by police at 2.6 times the rate as white people, and Black Americans experiencing mental health crises have been killed at almost twice the rate as white people in crisis, adjusting for population size and prevalence of mental illness by race.[48], [49]

Racialized inequities are maintained throughout the criminal legal system. For example, Black people comprise 32 percent of the state and federal prison populations[50] and 35.4 percent of the total jail population[51] even though they represent only 13 percent of the total United States population.[52] The lifetime risk of incarceration for Black males is 16 percent, and was as high as 50 percent at the start of the century. Meanwhile, the lifetime risk of incarceration for Native American males remains extremely high at 50 percent.[53] Between 2020 and 2021, the risk of mortality due to COVID-19 in Texas prisons was higher for Hispanic people and Black people compared to the incarcerated white population.[54], [55] These and other findings corroborate the existence of systemic racialized inequity in delivery of and access to healthcare services within prison and jail systems that mirrors racialized inequities throughout society, and these inequities may be aggravated during natural disasters, public health emergencies, and by consolidation and privatization of health services.[56], [57]

The 2019 mortality rate in state and federal prisons reported by the U.S. Department of Justice was 3.1 per 1,000 people,[58], [59] while the reported mortality rate in jails was 1.6 per thousand people.[60], [61] These higher mortality rates in prisons could reflect the aging population of people serving long-term or life sentences, as there are over 200,000 people currently serving life sentences in federal and state prisons.[62] Although there are greater percentages of Disabled people in jails than prisons, the percentage of people ages 55 and older is higher in prisons (15.7 percent, or 186,147 people, in prisons compared to 8.3 percent, or 55,300 people, in jails in 2022).[63], [64], [65] Because disability is more prevalent among incarcerated people ages 50 and older (44.2 percent to 59.7 percent in prisons and jails),[66] there is urgent concern about the quality of healthcare for the aging prison population.[67]

Although there has been a gradual decrease in the overall prison population in the United States during the past decade, the number of people ages 55 and older in prisons has not followed that trend, and comprises a growing portion of the total prison population.[68] The needs of older Disabled people who are incarcerated are less likely to be adequately met by privatized and private equity-owned correctional healthcare systems that have reduced staffing, have less oversight, and offer less individualized attention to patients. Parole hearing data analyzed by UnCommon Law,[69] an advocacy group for incarcerated people, found that Disabled people, including people with ambulatory disabilities, are granted parole at rates much lower (4.7 percent to 11.4 percent) than the general incarcerated population (17 percent).[70]

Disabled people who are incarcerated are the most vulnerable to inappropriate or substandard levels of care, as they have higher support needs or require specialty care that may be ignored or go unnoticed by unqualified staff, or staff that are instructed by management to minimize treatment. CNN documented numerous cases where Disabled people were jeopardized by privatized correctional healthcare, including the death of a woman whose diabetes went untreated by correctional healthcare staff despite her diagnosis being included in her medical history; people with HIV at the Gwinnett County Jail who were not given their medications; a person whose wheelchair was appropriated, necessitating an ER visit; people experiencing mental illness who were denied their prescribed medications; and at least two cases of people with cancer being given only over-the-counter pain medications in lieu of proper cancer treatment.[71]

Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (42 U.S.C. § 12132) states that “no qualified individual with a disability shall, by reason of such disability, be excluded from participation in or be denied the benefits of the services, programs, or activities of a public entity, or be subjected to discrimination by any such entity.”[72] The ADA thus applies to Disabled people who are incarcerated in state and federal correctional facilities and guarantees their right to access all correctional services and common spaces through the provision of reasonable accommodations or modifications if necessary. However, a 2016 report by Amplifying Voices of Inmates with Disabilities (AVID) found numerous ADA violations at prisons across the country, including inaccessible toilets, showers, and exercise spaces.[73] Moreover, the hostile, raucous, and unaccommodating environments in prisons and jails can be especially difficult for people with environmental sensitivities, including hyperacusis and electromagnetic hypersensitivity.[74] These diagnoses may be unrecognizable to medical staff, and even if they are acknowledged, the only alternative location to hold people in these facilities is often solitary confinement. The indiscriminate use of solitary confinement in prisons, jails, and detention centers severely aggravates mental health conditions and debilitates people with physical disabilities. The sensory deprivation, social isolation, and physical idleness for weeks or months on end all contribute to an increased risk of suicide.[75]

Diversion programs and other alternatives to incarceration, often based on coercive psychiatric treatment, are increasingly being touted by criminal legal reform advocates, “liberal” policy organizations, and mainstream mental health advocacy groups. This uncritical support has abetted the expansion of mental health courts in cities experiencing unprecedented levels of inequality and mass housing insecurity such as New York and Sacramento.[76], [77] In 2022, the same year that California Governor Gavin Newsom signed the CARE Act into law,[78] New York City’s Mayor Eric Adams issued a directive that authorizes “the removal of a person who appears to be mentally ill and displays an inability to meet basic living needs, even when no recent dangerous act has been observed.”[79] Both the laws in New York City and California are poorly disguised attempts to demonize, target, and scapegoat unhoused people and people experiencing mental illness for their governments’ failures to rein in housing costs and rampant housing insecurity. In other words, these are modern versions of the “ugly laws” masked as public health and public safety initiatives.[80] While such programs may divert people experiencing mental illness from jails, they also increase rather than lessen people’s involvement in the criminal legal system through case management and court-ordered treatment for low-level offenses that should not be criminalized or handled through the criminal legal system in the first place.[81]

About 44 percent of mental health court participants and about half of drug court participants fail their treatment programs and are sent back to jail or go to trial, often with worse charges against them.[82], [83] The lack of data made available to the public by state and city governments makes the efficacy of mental health courts in reducing recidivism difficult to evaluate, which warrants caution in the funding and expansion of such programs.[84] A 2020 literature review on mental health courts by the Council on Psychiatry and Law of the American Psychiatric Association, concluded, “Even after over two decades of research, questions remain regarding how MHCs meet their stated goals of reducing recidivism and improving psychiatric functioning. There are difficulties with sound experimental design in many of the published studies, a lack of transparency and detail about the specific procedures of the MHC(s) being studied, a lack of consistency about definitions of core outcome variables, and a publication bias toward ‘positive’ results.”[85]

It is clear that the expansion of the carceral state through court-mandated treatment, including psychotropic incarceration, is both a violation of human rights and self-defeating as a rehabilitation strategy.[86] Without government provision of housing, employment, and community-based services, such interventions only replicate the carceral logics of the 1960s, according to which the advent of antipsychotic medications were conceived as an operative replacement for asylums, in effect substituting physical restraint with chemical restraint.[87] The urgent fight against coercive intervention must therefore be heeded as part of the ongoing struggle for disability rights, and within the historical context of deinstitutionalization in face of the ever present threat of reinstitutionalization.[88] As the late disability rights advocate and co-founder of the American Association of People with Disabilities (AAPD), Justin Dart Jr., said a few years before his death, “No forced treatment ever.”[89]

The Political Economy of Incarceration

“A lot of people are talking about ‘criminal justice reform.’ Much of that talk is dangerous. The conventional wisdom is that there is an emerging consensus that the criminal legal system is ‘broken.’ But the system is ‘broken’ only to the extent that one believes its purpose is to promote the well-being of all members of our society. If the function of the modern punishment system is to preserve racial and economic hierarchy through brutality and control, then its bureaucracy is performing well” (Karakatsanis 2019).[90]

When critiquing the racialized and ideological project of mass incarceration, we often neglect to consider the political economy of the carceral industry even though these analyses are mutually constructive.[91], [92] The political economy includes the media narratives and political rhetoric that scapegoat, pathologize, and stigmatize Disabled people, as well as the public policies that direct taxpayer dollars to criminalize, medicalize, surveil, manage, confine, and punish poor and Disabled people, who are inconvenient reminders of the brutality of capitalism and white supremacy, or who are deemed unproductive or “surplus” members of society.[93], [94], [95] The ever-shifting carceral state finds ways to extract wealth from objectified and dehumanized people through forced labor and the creation of carceral and extra-carceral industries[96] that need managers, administrators, enforcers, and of course a fearful public that is willing to redistribute wealth to these constituencies.[97]

Prison policy in the United States can be considered a form of wealth redistribution towards, or more correctly, wealth hoarding by a class of mostly white, male constituents who are invested in maintaining or expanding a large carceral bureaucracy.[98], [99] In a globalized, multicultural society in which average white men have lost the most status and constitute the largest growing political threat,[100], [101], [102] it becomes economically and politically rational to “slap a uniform on them and assign them some minor or unnecessary task… at least that way, [the government] can keep an eye on them.”[103] Indeed, federal government spending that disproportionately allocates taxpayer dollars to law enforcement and national security makes racism and criminalization extremely lucrative for U.S. politics’ largest base of constituents.[104] (Congress itself is 75 percent white.) In the context of post-9/11 immigration securitization as well, “while the forces of globalization lead to a natural loosening of nation state borders and the transnational flow of labor back and force between nations, the criminalization of immigration attempts to act as a counterforce to these powerful movements, with the aim of closing the American border to the free flow of labor.”[105] In other words, criminalization not only redistributes wealth towards white people, but blocks the criminalized, racially marginalized populations from attaining wealth and status. In Alabama, for example, HB 56 not only enhanced police authority to stop and check an immigrant’s status, but also made it harder for undocumented immigrants to work in the state.[106]

U.S. “intelligence”[107] and national “security” agencies are about 74 percent white, and their offices are among the least diverse workspaces in the United States.[108] This is also true in the private tech sector, where executive teams are 83 percent white, and 80 percent male.[109] Federal defense contractors such as Lockheed Martin, which collectively receive several hundred billion taxpayer dollars per year from the federal government,[110] have historically tried to limit public access to their corporate diversity data despite requirements for federal contractors to abide by U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) reporting procedures. Estimates based on preliminary diversity reports obtained by Reveal through public records requests indicate that the executive ranks at these companies are disproportionately white and male.[111] As Fraser and Penzenstadler (2023) note, “The disparities highlight how tax dollars can reinforce gaps in wealth and opportunity for women and people of color.”[112] The defense contractor, Palantir, had zero women in its executive ranks just a few years ago, and in 2017, Palantir agreed to a $1.7 million settlement with the U.S. Labor Department for discriminating against Asian applicants during the resume screening process.[113], [114] According to the original lawsuit, there was one instance where 77 percent of 730 equally qualified candidates applying for seven engineering positions were Asian, and only one Asian applicant was hired.[115] Palantir’s co-founder, Peter Thiel, has argued that the company’s lack of diversity helps to reduce the “‘threat’ of subversion from workers.”[116]

These facts further reflect the tendency for these polities to seek wealth redistribution for themselves—both non-college-educated white men holding down blue-collar jobs, and the “privileged, white suburbanites walking around the streets in Southern California”[117], [118]—and to expand the carceral state by targeting and containing racialized and otherized groups, particularly Black people and brown people, as well as Disabled people.[119], [120] It’s not a coincidence that the economy, including concerns about inflation, and immigration were among the most pressing issues for voters in the 2024 presidential election, giving the edge to Donald Trump who won 80 percent of the voters who named the economy as the most important issue, and 90 percent of the voters who mentioned immigration as the most important issue.[121] Trump has pledged to intensify mass deportation at an unprecedented scale once he retakes the White House.[122]

In 2017, under the Trump administration, ICE launched its Extreme Vetting Initiative, since rebranded as the Visa Lifecycle Vetting Initiative, which initially planned to use artificial intelligence to monitor targeted immigrants’ social media accounts to determine whether they would become “contributing members of society”[123] or criminals. ICE hoped to generate 10,000 investigative leads per year, i.e. they were intentionally seeking to find 10,000 new people to target every year.[124] The program is run by the Counterterrorism and Criminal Exploitation Unit of Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) and is under contract with General Dynamics, one of the largest defense contractors in the world. General Dynamics’ corporate executive board is 90 percent white.[125]

Through the War on Drugs, local police departments have become militarized and incentivized to increase drug-related arrests targeting Black people and brown people under a federal disbursement scheme that made their funding contingent on meeting arrest quotas.[126] As Alexander notes, “The officers were under tremendous pressure from their commander to keep their arrest numbers up, and all of the officers were aware that their jobs depended on the renewal of a federal grant.”[127] Karakatsanis explains, “As the bureaucracy expands, it employs larger and larger numbers of police officers, prosecutors, probation officers, defense attorneys, prison guards, contractors, and equipment manufacturers. People working in the system become dependent on its perpetuation for their livelihoods and even their identities.”[128], [129]

Exploring the relationship between crime and incarceration, the MIT economist, Peter Temin, found greater explanatory power by mathematically modeling crime rates as a function of incarceration (rather than incarceration rates as a function of crime), noting that incarceration, particularly in economically disadvantaged and racially marginalized communities, increases crime.[130] Removing just two or three breadwinners, caregivers, or elders in a community can starve neighborhoods out of social and financial capital, disrupt networks, separate families, increase alienation, and have other subversive effects on families and neighborhoods that increase reliance on policing, which in turn increases rates of incarceration.[131], [132], [133] In this era of mass incarceration, billions in taxpayer dollars have been invested into law enforcement and carceral infrastructure simultaneously with disinvestment from subsidized housing, public education, and community health services. Furthermore, incarcerated people and people who are formerly incarcerated are permanently stigmatized and legally excluded from opportunities for education, housing, and employment.[134], [135] Mass incarceration thus not only targets poor, racially marginalized people, but further entrenches crime and poverty in the United States while enriching white people.[136] The model of crime as a function of incarceration helps to explain how policing is a self-sustaining industry. It manufactures crime, which increases demand for more policing.

To provide some perspective on just how much United States culture and its economy are centered around carcerality, an article in The Hollywood Reporter reveals that crime and law enforcement procedurals comprise nearly 20 percent of scripted television programming, outnumbering all other genres.[137] A scathing 2020 report by Color of Change notes that “the crime genre glorifies, justifies and normalizes the systematic violence and injustice meted out by police, making heroes out of police and prosecutors who engage in abuse, particularly against people of color.”[138] Alexander observes, “These television shows, especially those that romanticize drug-law enforcement, are the modern-day equivalent of the old movies portraying happy slaves.”[139] According to the Urban Institute, in 2021, state and local governments spent $274 billion, or 7.5 percent of total expenditures, on police, corrections, and courts, which is four times the amount spent on housing and community development. Between 1977 and 2021, spending on the correctional industry, which includes prisons and jails, increased 346 percent, which is higher than any other category of expenditure increase except for public welfare.[140]

Private equity firms are increasingly using their financial clout and political connections both to take advantage of our society’s reliance on carcerality and to expand the carceral state. For example, the President of the National School Safety and Security Services, Ken Trump, wrote that private equity firms have recently started buying up businesses that provide security technology and services to K-12 schools. Trump observed that investors are “dumping millions into security hardware, product, and technology companies that the investors believe will flourish by capitalizing on public fears of school shootings.”[141] Ed tech companies like Bark,[142] Gaggle,[143] and Securly,[144] which are digital surveillance platforms extremely embedded in K-12 schools, are all private equity-owned or backed. As Higdon and Butler write in Teen Vogue, “These technologies have been sold to K-12 schools across the US with promises of greater safety and improved academic outcomes… But these technologies have failed to deliver on their promises. Worse, what they have delivered is a blow to some of the most basic requirements of quality education and an unprecedented violation of student privacy. The impact is particularly acute on communities of color, who are far more likely to attend high-surveillance high schools than white students.”[145]

The private equity company, H.I.G. Capital, which owns the prison healthcare company, Wellpath, also owns Symplicity, which is the second largest student case management software company in the United States.[146] Contracted with over 1,000 institutions in higher education, Symplicity helps university administrations to deputize community members to surveil students and report “suspicious” behaviors, a mandate which often targets neurodivergent, Disabled students, and other marginalized students.[147] Private equity firms also control approximately a third of United States methadone clinics, and are leveraging their market share to lobby Congress to prevent other medical providers from being able to dispense methadone (a drug used to treat opioid addiction), thus limiting access to treatment that can save lives as well as help people to stay out of the criminal legal system.[148]

Agencies like the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) continuously seek ways to use technology to expand the carceral state, and tech companies like Amazon, Microsoft, and GitHub will always jump at the opportunity to supply these technologies to the government for a piece of those taxpayer dollars.[149] The only limits to the expansion of these bad policies and harmful technologies are what an informed public will tolerate, which is why it is important for disability advocacy organizations to remain vigilant and to work in cross-movement and cross-racial solidarity with other civil rights and social justice groups.[150], [151]

Although less costly and more effective alternatives to incarceration, policing, and mass surveillance exist, these systems are maintained so that all the benefits go to those invested in these institutions, while marginalized people, including Disabled people, are treated as objects for their profit making.[152] Transformative justice approaches that reimagine how communities prevent and respond to harm can help to ensure that root causes of violence are addressed; that state tools are never brought into the justice process to replicate oppressive power dynamics; and that nobody is excluded or treated as disposable in the seeking of safety and accountability.[153] However, transformative justice is a community-based approach that requires commitment from all parties involved to seek alternative ways of healing. The largest barriers to transformative justice are the people who are materially or emotionally invested in systems of punishment, exclusion, and restoration.

I. Correctional Healthcare

Privatization and the policies that abetted mass incarceration since the 1980s are interlinked. More punitive and mandatory minimum sentencing under President Reagan’s War on Drugs and its escalation under subsequent administrations put hundreds of thousands of Black people in prison. Correctional healthcare costs skyrocketed as the prison population expanded and grew older.[154], [155] Concurrent with President Reagan’s demonization of government and taxes, and public indifference towards the growing proportion of Black people in prisons and jails in the 1980s,[156] privatization of correctional facilities became “politically permissive” and accelerated in the 1990s under subsequent administrations.[157] The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, also known as the 1994 Crime Bill, passed by the Clinton administration, provided federal money for states to build more prisons and incentivized states to incarcerate more of their populations.[158] The now-debunked “superpredator” theory that was concocted by Princeton University professor John Dilulio and eagerly propagated by politicians, academics, and news publishers in the years following, legitimized the increased policing and incarceration of young Black men.[159]

The private correctional health industry that emerged, “a system that facilitates the illegal treatment of citizens in the custody of the state,” was not propelled solely by economic forces, but was rather “a deliberate decision by local government legislative bodies to subject a particular constituency to market forces.”[160] In this system, contractors are incentivized to provide the minimum care due to fixed reimbursement schemes, while the indemnification clauses in their contracts shield government agencies from costly lawsuits and disincentivize the provision of effective oversight. Meanwhile, corporations and private equity firms are better equipped to game the legal and regulatory system to survive lawsuits and evade damage to their reputations, both through limited liability and bankruptcy laws and by nature of being private entities.[161] Saldivar and Price (2015) note that private contractors are not bound by Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) laws, and all attempts to pass legislation in Congress to remove private prison companies from FOIA exemption have been foiled by private prison industry lobbyists.[162] Because private equity firms, as opposed to publicly traded firms, are not even accountable to shareholders, this removes further layers of transparency, making these companies fairly immune to shareholder activism, for example.

Over 60 percent of United States jails currently use private contractors to deliver healthcare services to incarcerated people.[163] County governments, particularly in smaller counties, are often lured by contractors’ promises of minimizing the risks and mitigating the costs involved with correctional healthcare, especially from potential lawsuits.[164], [165], [166] As Deitch (2020) notes, “the desire to avoid litigation is a major motivator” for county sheriffs, “since county officials hold the purse strings for the sheriff’s department as well as the ultimate financial liability for any lawsuits.”[167] In practice, however, some county jails have been more exposed to lawsuits by outsourcing healthcare even while the contractors remain shielded.[168] A study by Reuters of recent deaths at over 500 city and county jails found that facilities that contracted with private correctional healthcare companies had higher mortality rates than jails with publicly operated healthcare.[169]

One of the most egregious examples of the ways that private equity-owned prison companies shield themselves from liability is the case of Corizon Health, now known as YesCare, which has had multiple private equity owners since 2007.[170] There are currently over 500 active lawsuits against Corizon for a litany of issues, with a variety of claimants including state governments, hospitals, formerly incarcerated people, and former employees, as well as a former Corizon CEO. The claimants allege unpaid invoices, neglect, wrongful injury, wrongful death, and unlawful termination among other violations.[171], [172]

In 2022, Corizon split into two companies, with its assets including all its government contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars transferred to YesCare, and its liabilities, including the money owed to creditors, shifted to a shell company, Tehum, which immediately filed for bankruptcy.[173] If the bankruptcy is approved by the federal courts, it would essentially shield Corizon’s assets from creditors and vastly reduce the settlements awarded to the claimants. And, as noted by Schwartzapfel (2023), the indemnity clause that would have protected government agencies from lawsuits would no longer hold, because Corizon was split into two companies.[174] Corizon’s “bad faith” tactics have already left state and local government agencies with liabilities in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, and is just one example of how troubled companies, under private equity management, will attempt to avoid their contractual obligations.[175] In 2024, the Department of Justice supported a motion to dismiss Corizon’s bankruptcy case, suggesting that maybe Corizon has pushed the envelope a bit too far even for an industry that routinely pushes the limits of shady business practices.[176]

It’s clear that the business model for private contractors in the correctional healthcare system is not much different from that in other healthcare sectors. Companies may seek to maximize margins by taking advantage of flat fee contracts that incentivize them to provide the minimal services, including denying or delaying medical care to people in custody.[177] Per-prisoner fee contracts can also result in delivery of services that are not scaled to patients’ needs, as in the case of the Illinois Department of Corrections’ decades-long history of “shoddy care” with the private company, Wexford Health Services, which “may have cut short the lives of some inmates.”[178] For example, because contracts often stipulate that the companies must pay a share of the cost for emergency care and other off-site medical care, providers are incentivized to treat patients in the jail infirmary even when a higher level of care is necessary.[179] Senior medical staff at these companies have corroborated that they have been told by upper management to avoid sending patients to the emergency room. Corizon also allegedly paid bonuses to doctors anytime they averted an ER visit.[180], [181] A report by The Pew Charitable Trusts noted, “Because of the potential to incur substantial and unpredictable expenses, vendors can be apprehensive about assuming financial responsibility for patient hospitalizations.”[182] A recent Reuters study examining the differences between private correctional healthcare and publicly managed correctional care found a 53 percent decrease in costs related to hospital visits one year after Corizon took over at one jail.[183]

Private Equity in Prisons and Jails

In 2014, 26-year-old Madaline Pitkin died at Washington County Jail in Oregon. The jail had contracted out its medical services to Corizon Health. According to depositions for the lawsuit, the jail was chronically understaffed, and unqualified staff were assigned to the sickest patients. Medical staff minimized Pitkin’s symptoms and failed to adequately monitor her vital signs during the seven days that Pitkin was held in the jail, where she was detoxing from heroin. Pitkin requested help on four separate occasions, writing in her last request, “I feel like I am very close to death. Can’t hear, seeing lights, hearing voices. Please help me.” She died the next morning of severe dehydration. It was determined that a simple administration of I.V. fluids would have saved her.[184]

In 2016, Henry Clay Stewart died at the Hampton Roads Regional Jail in Portsmouth, Virginia, after waiting almost 30 days to receive medical attention for a perforated ulcer.[185] Twenty-five more incarcerated people have died there since 2015, and the jail was finally closed this year.[186] A scathing 45-page report by the U.S. Department of Justice found that Hampton Roads Jail, which was contracted with Correct Care Solutions (CCS), now part of Wellpath, had violated people’s constitutional rights by failing to provide adequate medical care, and violated the ADA by placing prisoners experiencing mental illness in prolonged solitary confinement, which exacerbates mental health conditions.[187]

The two largest providers of correctional healthcare services in the United States are YesCare and Wellpath,[188] both currently owned by private equity. YesCare, formerly known as Corizon Health, Inc., was acquired by the private equity firm, Blue Mountain Capital Group, from Beecken Petty O’Keefe & Company, also a private equity firm, in 2017; was then sold to the holding firm, Flacks Group, in 2020,[189] which subsequently sold Corizon to the holding company, Perigrove, in 2021.[190] The frequent changes in ownership are very much a part of the private equity playbook. Although firms extract as much capital as they possibly can from these companies before selling them off, the companies often retain value for the next buyer, because industries like correctional healthcare operate in low competition markets with captive audiences and steady revenue streams from government contracts.[191]

Private equity firms frequently buy out distressed companies that have accumulated long lists of lawsuits and creditors. To help those companies stay solvent, private equity firms will resort to cost cutting, bankruptcy proceedings, or other legal maneuvers. In every case, rebranded companies continue to receive new government contracts, often claiming that they are not the same company despite often retaining the company’s management, standard operating procedures, and assets.[192] In 2022, for example, the Alabama Department of Corrections extended its contract, worth $125 million, with YesCare despite three other companies that placed bids.[193] This year, Maryland opted not to renew its jail and prison healthcare contract with YesCare, despite the company’s claims that they are “not affiliated in any way” with Corizon.[194], [195] Arguably, private equity firms, like dung beetles, may be performing an important ecological function in the economy, by recycling distressed companies. But, it’s also plausible that private equity firms enable highly problematic business practices by helping these companies and the people that manage them to avoid financial, legal, and moral accountability.

In 2018, Correct Care Solutions (CCS) merged with the private equity-owned Correctional Medical Group Companies (CMGC), and the newly formed conglomerate was rebranded as Wellpath, which is owned by the private equity firm, H.I.G. Capital.[196] Prior to its acquisition by H.I.G., there had been nearly 1,400 lawsuits filed against CCS.[197] A CNN investigation of over 120 facilities contracted with Correct Care Solutions found widespread lack of training among its employees and chronic understaffing issues that led to substandard care and upwards of 70 preventable deaths between 2014 and 2018.[198] The Pierce County Jail in Tacoma, Washington, terminated its contract with CCS after a little over a year, noting that “[CCS’] performance under the contract was morally reprehensible” with frequent instances of improperly licensed medical professionals working at the clinic, lost or missing medical records, and weekly turnover of staff.[199] Other jails that are currently contracted with Wellpath continue to spawn lawsuits, including a recent case involving a 25-year-old’s suicide at Davidson County Jail in Nashville, Tennessee.[200]

The majority of Wellpath’s business is in providing healthcare services to jails, but H.I.G. Capital also owns TKC Holdings, which provides cafeteria, commissary, and telecommunication services to correctional facilities and detention centers.[201] In his book, Plunder: Private Equity’s Plan to Pillage America, Brendan Ballou describes how private equity firms exploit incarcerated people as a “captive audience” by providing bare minimum food and phone services and gouging people in prisons and jails on service fees.[202] Ballou found instances of people being charged upwards of $12 for 15-minute phone calls, forcing cash-strapped people, the majority of whom cannot afford lawyers,[203] to either forgo communication with their families for months on end or have their meager wages garnished by these private companies. The legal scholar, Alec Karakatsanis, equates these practices to a modern-day form of convict leasing, where “[incarcerated people] work long hours every day in often dangerous conditions with miniscule wages to produce products for private corporations and government entities so that prisoners can afford to purchase basic necessities sold by other private corporations inside prison walls.”[204]

Just as disturbing perhaps is the surveillance capabilities that are built into the telecommunications services provided by private equity-owned contractors like Telmate. Prisons, jails, and ICE detention facilities that use Telmate’s video call technology record the conversations and user data of people on both sides of a call, including their dates of birth, home addresses, and Social Security numbers, and provide this information to law enforcement.[205] In 2017, Telmate was acquired by the private equity-backed company, ViaPath Technologies, formerly known as Global Tel Link (GTL).[206], [207] In 2020, Telmate’s data was breached, and the personally identifiable information of thousands of incarcerated people and their families were posted on the dark web.[208]

Often, meals provided by private contractors are not just the bare minimum quality, but actually unsafe to eat, including rotten, moldy, and maggot-infested food. The companies providing cafeteria services spend about $1.29 per meal, and often try to cut costs by serving questionably sourced food.[209] In some cases, contractors were discovered to be sourcing food from suppliers who explicitly marked their products as “not fit for human consumption” or “for further processing only.” But, because private equity firms often own both the cafeteria and commissary services at these facilities, it doesn’t matter to the contractors if the food served is inedible, as it encourages people to buy food from the commissary at a great markup.[210] David Fathi, of the American Civil Liberties Union, observes that “Market forces don’t operate in the prison context for the reason that prisoners have absolutely no consumer choice.”[211]

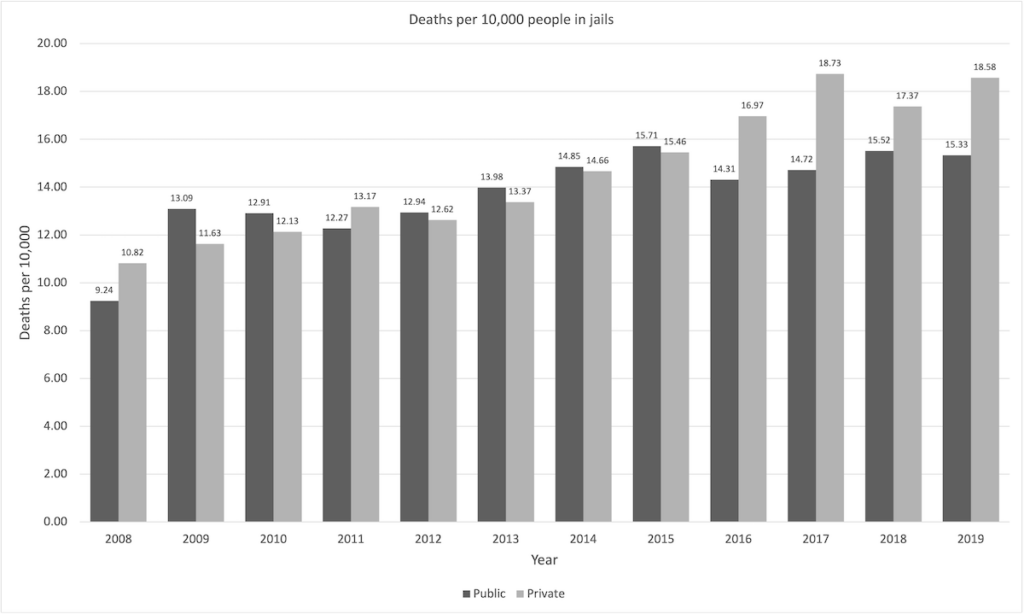

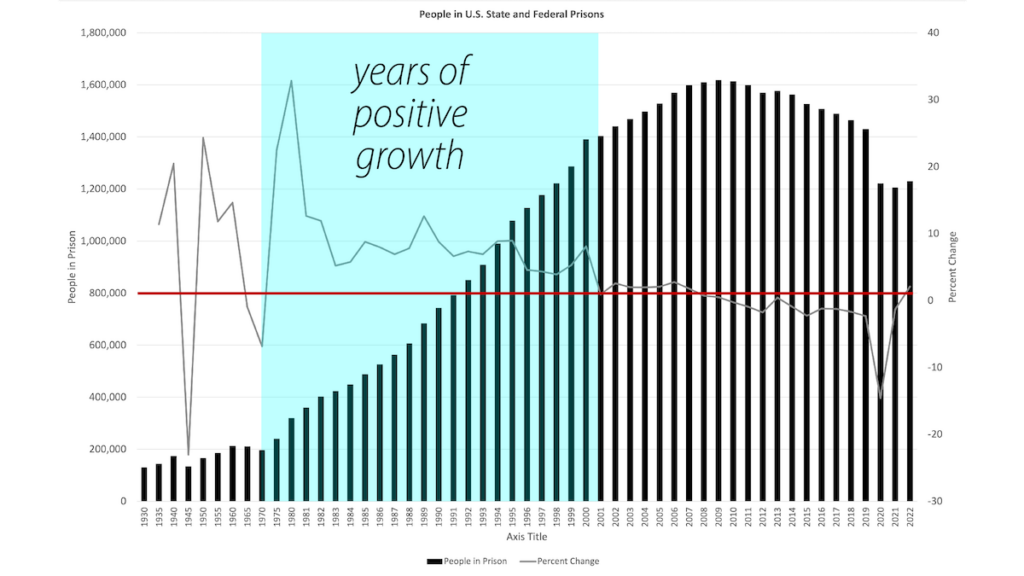

There are no existing academic studies comparing the quality of privatized correctional healthcare to government-provided services,[212] but a recent study by Reuters analyzing data from over 500 large jails found that contracting with private correctional healthcare companies was associated with 18 to 58 percent higher risk of death for incarcerated people.[213] The mortality rate at jails with publicly managed healthcare decreased 2.4 percent from 2015 to 2019, while the mortality rate at jails that contracted out healthcare to private companies increased 20.2 percent in that same time period. For all jails, the mortality rate has increased about 70 percent since 2008. (See Figure 1 below.)

Although Wellpath and YesCare are the largest correctional healthcare companies in the U.S., it’s far from the case that they hold a monopoly on abuse, corruption, and neglect in the correctional healthcare industry. Other for-profit, non-private equity-owned companies, such as Advanced Correctional Healthcare (ACH) and NaphCare Inc., are also competing for these lucrative contracts with county jails and state prisons and are equally plagued with histories of wrongful deaths in custody.[214] At the Washoe County Jail in Reno, Nevada, ten people who were incarcerated died within the two years that NaphCare took over responsibilities for the jail’s healthcare services after winning a $5.9 million per year, no-bid contract. The death rate was 400 percent over the national average for county jails.[215] The Reuters study mentioned earlier looked at data for the five largest private contractors, and the analysts found that two non-private equity-owned private companies, NaphCare and Armor, had the worst outcomes in the three year period from 2016 to 2018.

Figure 1. Number of deaths per 10,000 people in United States jails. Through public records requests, Reuters journalists gathered data on 7,571 deaths that occurred at 523 jails between 2008 and 2019. The yearly death rate was calculated by dividing the number of deaths by the average daily population. Image description: A clustered bar chart showing the number of deaths per 10,000 people in jails with publicly run healthcare (left bars) and jails with privatized healthcare (right bars) for each year between 2008 and 2019. There is a generally increasing trend in the number of deaths from 2008 to 2019 for jails with privatized healthcare and for both jail types combined. Data source: Reuters.[216]

Because consolidation has reduced competition in the correctional healthcare market, it can be a challenge for city and county agencies to find alternative providers when companies like Wellpath may be the only provider available in an area. This was the case in Forsyth County Jail in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where two preventable deaths occurred in the span of a month in 2017.[217] When it came time to find a new contractor that year, Correct Care Solutions was the only bidder.[218] The Pierce County Sheriff’s Department in Tacoma, Washington, also cited consolidation as the reason its hand was forced into signing a contract with Wellpath/Correct Care Solutions, noting that “with CCS buying out so many other correctional healthcare companies, Pierce County’s options for a contracted health care provider were significantly diminished.”[219] The Montgomery County Jail in Conroe, Texas, did manage to find another contractor, Southwest Correctional Medical Group (SWCMG), when it discontinued its contract with CCS in 2017, only to be forced to work with CCS again when Wellpath (formerly CCS) acquired SWCMG in 2018.[220]

In recent years, some counties that did not renew their contracts with private correctional healthcare companies have opted instead to collaborate with local university medical centers, and others are looking to establish publicly managed services, but it can take years for government agencies to build up the necessary infrastructure and staffing to replace the private contractors that have been operating at these sites for years or even decades.[221], [222], [223] State prisons, as well, often have a bleak choice of contracting between private equity-owned contractors or other privately owned companies like Centurion, Wexford Health Sources, and VitalCore Health Strategies, among just a handful of other companies. In response to public pressure, the Massachusetts Department of Correction dropped Wellpath this year and awarded a five-year, $770 million contract to VitalCore Health Strategies even though, as The Boston Globe reports, VitalCore’s record is hardly spotless.[224]

Prisons and Jails Are Not the New Asylums

“Whenever I hear somebody say that mental health is the issue when it comes to violence, I know inherently they are not interested in solving the problem at all” (Barbarin 2023).[225]

According to 2011 federal survey data, about 15 percent of people in state or federal prisons, and 26 percent of people in jails reported experiencing serious psychological distress.[226] In total, between 37 and 44 percent of incarcerated people are experiencing mental illness,[227] and almost half of incarcerated Disabled people have previously received services in congregate care settings.[228], [229] Since the very beginnings of mass housing insecurity in the 1980s, the predominant narrative deployed by politicians and mainstream criminal legal reform advocates to explain these troubling statistics has been that prisons and jails have become de facto warehouses for people experiencing mental illness, along with a perfunctory acknowledgment that these institutions are not adequate places for Disabled people who need healthcare and shelter.[230], [231], [232], [233] The commonly peddled thesis about why there have been increasing numbers of unhoused people and incarcerated people with mental illness is that as we began shutting down the asylums in the 1950s, Disabled people ended up on the streets or in jails, because they presumably need to be in psychiatric hospitals.[234], [235]

Deinstitutionalization as a movement was already underway by the 1950s. The Community Mental Health Act of 1963, signed by President Kennedy, formalized the nation’s transition from custodial institutionalization to community-based treatment centers. Although these community services were never properly funded, many of the people released from psychiatric institutions in the 1950s through the 1970s never ended up on the streets, although some did end up in nursing homes, group homes, and single-room occupancy (SRO) units, which are a type of affordable housing.[236], [237], [238] Conjecturing a causal link between deinstitutionalization and mass incarceration requires taking as fact the erroneous assumption that the same population was transferred from one carceral system to another, but this is not borne out in demographic studies of the populations held in these different systems.[239], [240], [241] A 1986 study of the unhoused population in Los Angeles, for example, found that less than 30 percent had ever been institutionalized, but because of methodological flaws, even these early studies tended to oversample the subpopulations of unhoused people who were experiencing mental illness and using substances.[242]

Houselessness, and mass housing insecurity more broadly, didn’t become a national issue until the 1980s when Reagan- through Bush-era policies that dismantled social safety nets based on racialized discourses of the “welfare queen,” combined with laws that expanded policing and prison systems based on discourses of “Willie Horton” and the “dangerous Black man,” targeted different populations to fill the void left when one carceral system (the asylum) shut down and others expanded, creating new generations of incarcerated people.[243], [244], [245], [246], [247] In the 1970s and 1980s, the mass demolition or conversion of SRO buildings, where some formerly institutionalized people resided, into luxury apartments, certainly displaced many people into houselessness.[248] Munshi and Willse (2007) note how, immediately following Reagan’s welfare retrenchment, policing and mass incarceration expanded in order “to manage the social unrest and disorder that results from the dismantling of the social safety net.”[249] During this same time period, Harvard University scholars, George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson, as well as journalists like Malcolm Gladwell, author of The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, popularized the narrative of “broken windows” policing,[250] which rationalized aggressive policing of Black people, including the use of stop-and-frisk, and the criminalization of minor offenses as necessary to prevent crime from spreading.[251], [252]

Critics of deinstitutionalization often take a narrow and ahistorical perspective by failing to consider how lack of community services, housing, and employment increase the risk of entanglement with the criminal legal system, particularly through interactive effects with stigma and racism, and how marginalization, poverty, criminalization, policing, and incarceration are inherently debilitating and (re)traumatizing. Criminal legal reform organizations and mainstream political advocacy groups that receive funding from billionaire philanthropists, such as the Koch brothers, are perhaps also inclined to propagate narratives of individual blame and pathology to deflect from the political manufacturing of the affordable housing crisis and mass incarceration.[253] While the importance of investment in community-based services must not be understated, a singular focus on the lack of mental health services can be as misleading as other critiques of deinstitutionalization, particularly in its purported relations to crime and houselessness, in that it overly medicalizes the sociopolitical problems of mass housing insecurity and unaffordable housing in the United States.[254], [255] As the anthropologist, Arline Mathieu writes, “Broadly speaking, the administration’s continued identification of homelessness as a medical problem of individuals served to divert attention from homelessness as a systemic economic and housing problem.”[256]

While President Reagan repealed major provisions of the Mental Health Systems Act of 1980, further gutting funding for community-based mental health services, his administration also cut public assistance benefits and funding for low-income housing by 80 percent. In New York City during the 1980s, the availability of apartments renting for $300 or less per month decreased by 72 percent, and the number of unhoused people more than doubled by the end of the decade.[257] Unhinged greed and wealth accumulation became culturally celebrated in films like Wall Street, and criminalization of poor and Black people intensified, as evidenced by the staggering 115 percent growth in the New York Police Department budget, a rate not even matched in the following decades.[258] Schermerhorn (2023) observes that “a prison sentence could devastate a Black family economically, slashing its wealth by two-thirds. Fines, fees, lost income, and family debts crushed Black Americans.”[259] In addition to Reagan’s tough-on-crime policies that disproportionately targeted Black Americans, the administration was instrumental in destroying unions and constricting the role of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, both important apparatuses that provided a safety net for Black workers.[260] The sociologist, Robert B. Hill, writes that “the sharp increases in unemployment, poverty and one-parent families among [Black Americans] were due, in large part, to the structurally discriminatory effects of major economic forces and policies” that erased “the social and economic gains achieved by black families during the 1960s.”[261]

Beyond the medicalizing narratives of treatment or lack thereof, the dismal outcomes for people experiencing mental illness and houselessness during the past four decades, particularly people who became criminalized and incarcerated, must be considered in context of the far more consequential impacts of racism and poverty.[262] As the late author and University of California neuroscientist, James Fallon, explained as he contemplated the trajectory of his own life as a well-regarded psychopath, what largely separates incarcerated, neurodivergent people from those who become doctors, politicians, and corporate executives[263] is the latter group’s access to social and financial capital. Rapidly growing income inequality in the 1980s that coincided with Reagan-era neoliberalism and tough-on-crime policies that especially targeted Black families almost guaranteed that prisons and jails would be filled in the following decades.[264], [265] As the author and activist, Kimberly Jones, wrote a year after the police killing of George Floyd, “One of the things one must consider about being Black in America is how LUCKY any of us has to be to get to adulthood without so much trauma and so many scars we can barely function.”[266] It should not be a surprise that there is a high prevalence of disability among the marginalized and criminalized populations that are trapped in these systems, as that was always the intended impact of mass incarceration.[267], [268]

Studies on the health impacts of detention on refugees and asylum seekers are helpful in shedding light on the causal link between incarceration and disability since studies on migrant populations remove any supposed links and possibly confounding associations between mental illness and crime/arrest. A recent meta-analysis found that depression is present in about 68 percent of immigrant detainees while PTSD has a prevalence rate of 42 percent.[269] Because of experiences with pre-migration trauma and peri-migration insecurity, policing, and stigma, migrants generally experience depression and PTSD at high rates,[270] but studies consistently find that prevalence rates of mental illness for detained immigrants are much higher than rates in the non-detained migrant population.[271], [272] Because undocumented immigrants are generally arrested or detained for reasons distinct from the non-immigrant population, the research findings suggest that incarceration by itself negatively impacts mental health.[273] One study of Iranian and Afghani refugees found that these effects persisted after being released from detention.[274] Collectively, these findings on the impacts of detention on immigrants’ mental health suggest that incarceration is in and of itself debilitating and that criminalization leads to incarceration. Together, criminalization and incarceration contribute in no small part to the higher rates of mental illness and disability among incarcerated people. This is why we need to stop saying that “the largest treater of mental health is the U.S. criminal justice system,”[275] because the evidence is abundant and clear that there is no healing or treatment that can occur in a system where marginalized people are constantly exposed to policing, surveillance, arrest, trauma, erasure, and containment.

Mental Health Courts and “Alternatives to Incarceration”

Reginald “Neli” Latson is an autistic Black man, now in his thirties, who lives in Virginia. In 2010, when he was 18, he was sitting outside the Stafford County library, where he liked to hang out. It was still early morning, so Latson was waiting for the building to open. That’s when someone saw him and called the sheriff’s office, reporting that there was a “suspicious male, possibly in possession of a gun.” When the school resource officer came by to investigate, he didn’t find a gun, but he was assaulted as he tried to grab Latson, who was trying to leave. Latson was arrested, charged, and sentenced to ten years in prison. After five years in prison and hundreds of days in solitary confinement, he was released on parole in 2015, and was granted a pardon in 2021, though Latson still has a felony conviction on his record. When Governor Terry McAuliffe pardoned Latson, he correctly observed that Latson “never should have been sent to jail,” but curiously added that, “He needed medical care for his autism.”[276], [277], [278]

Diversion programs, “problem-solving courts,” mental health courts, and most recently, CARE courts, were initially conceived in the 1990s as an alternative to incarceration for people with disabilities. As a relatively new industry with scant science behind its development, diversion programs vary widely in their implementation, including qualifications for entry, duration of treatment, availability of community services, and operationalization and measurement of success or completion.[279] Despite having a semblance of voluntariness about participation, the common thread in all diversion programs is coercive treatment with the threat of reincarceration or conservatorship for noncompliance.

People held within the criminal legal system traditionally have had two entryways into diversion programs. Pre-booking diversion occurs when police detain an individual without charging the person with a crime. Post-booking diversion occurs either in court or in jail, after the person has been charged.[280] The intent of post-booking diversion programs and mental health courts is to help people who have been arrested for low level offenses to avoid jail or prison time. In 2022, the Mental Health Diversion law in California was revised by Governor Gavin Newsom to require that judges now presume that mental illness is a factor in all crimes being considered for prosecution and to consider eligible cases for pretrial diversion.[281], [282] Under the revised law, the number of petitions granted for mental health diversion increased 395 percent, from 947 in 2020 to 4,687 in 2023.[283] In San Francisco alone, over 300 petitions have been granted since 2020, but without an attendant decrease in the number of people incarcerated in the city’s jails. These dismal results prompted the MacArthur Foundation this year to suspend its Safety and Justice Challenge grants to the District Attorney’s Office, which have totaled over $3 million since 2021.[284] In its letter to the San Francisco District Attorney, the MacArthur Foundation noted that it was “particularly concerned about the increases in [San Francisco’s] jail population and racial and ethnic disparities.”[285]